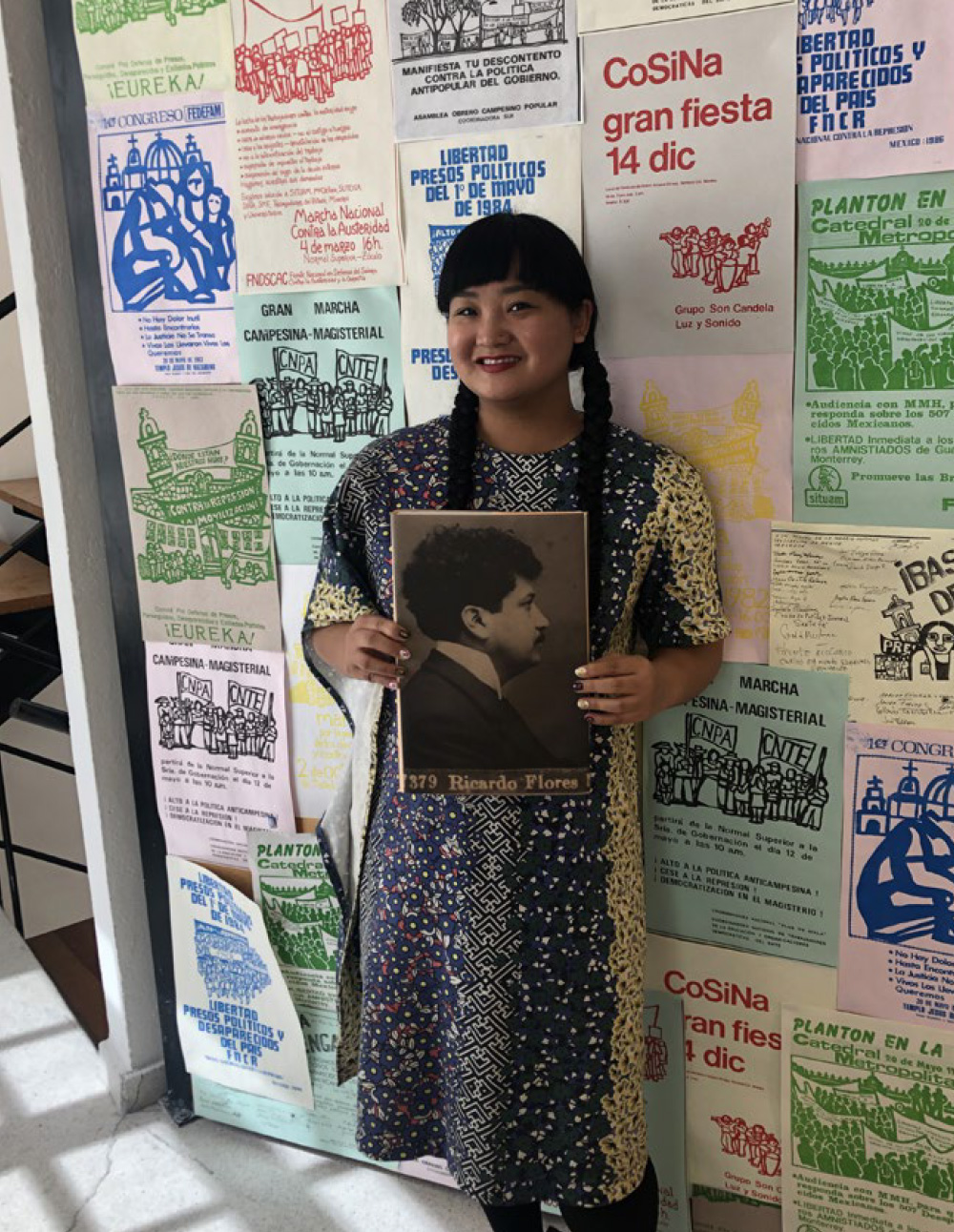

T-Kay Sangwand with the Regeneración facsimile at Casa del Hijo de El Ahuizote. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand.

T-Kay Sangwand is a certified archivist, librarian, and DJ. She is currently the librarian for digital collection development at UCLA Library and holds a MLIS and MA in Latin American Studies from UCLA. She is currently a 2020–2022 Rare Book School / Mellon Foundation Cultural Heritage Fellow. Since 2001, Sangwand has worked in community radio and currently hosts the program “The Archive of Feelings” on www.dublab.com.

This interview was conducted in April 2022. It has been edited for clarity.

Corinna Zeltsman Hi T-Kay. I’m so happy that we get to talk today about your fascinating work. You recently organized this really exciting virtual series for the Biblio-graphical Society of America on radical publishing in Mexico City,1 and in talking about the series during the lecture that you gave for CalRBS [California Rare Book School],2 you presented yourself as a relative newcomer who stumbled into the world of radical publishing through your current position at UCLA Library. However, given what I know about your previous intellectual, artistic, and professional background, I think there’s more to the story. Tell us about how your trajectory led you to an interest in radical publishing.

T-Kay Sangwand Yeah . . . so how far back should I go? [laughs] There are a lot of threads that seem disparate, but I do think that they come together in a way that makes sense after you look at them all together, so I’m going to go back to high school actually.

I’ve always been a music head. In high school I got introduced to the world of punk rock and riot grrrl, specifically. Riot grrrl was a subculture within punk that focused on female participation in the punk scene, which was very heavily male-dominated. There was this essay “Jigsaw Youth,” written by Kathleen Hanna of [riot grrrl band] Bikini Kill, and that was my introduction to zine culture and feminism. That’s what I credit for raising my feminist consciousness—which informed my decision to major in gender studies when I went to college.

When I got into this music I was also searching for the community around it. As a high school student I would listen to the radio on my Walkman, and one day I was scrolling up and down the dial and found a college radio station [KSPC 88.7 FM] that played a lot of riot grrrl, in addition to other indie genres. I befriended many of the DJs there who ended up inspiring me to apply to the Claremont Colleges, which is where the radio station KSPC was based. I decided to major in gender studies, and I attended Scripps, the women’s college, because I thought that would be a really great environment to pursue those studies. I minored in Latin American studies, and so my focus for much of undergrad was looking at gender in social movements in Latin America. That’s also when I started working in my college library [Denison Library]. I started working in the library just as a job, but as I ended up working there for almost all of my college experience it prompted me to think, “Wait, what does it take to work in a library?” The librarians [at Denison] gave me some guidance about applying to library school.

When I started library school, I thought I would become more of a traditional subject specialist, but then I took a class on archives [with Anne Gilliland] and that showed me how archives could really be used as a tool of empowerment for marginalized communities. Considering what I had studied—social movements in Latin America—I thought, “Oh, maybe archival work is a way to support these types of movements, just from a totally different angle.” When I was in [the UCLA MLIS] program I really sought out opportunities to work with histories that are typically marginalized from the historical record, and so I worked on processing lesbian archival collections from Los Angeles, records related to Japanese incarceration during World War II, documentation on the LA Uprising, and even looking further back to leftist and communist organizing in Los Angeles in the ’30s. I was always seeking out opportunities to gain technical archival skills, but also in service of these marginalized histories. That’s what led me to my first professional job. I remember when UT [University of Texas] Austin posted the job for human rights archivist, many people sent that listing to me and encouraged me to apply. That’s where I really got to put into practice all the technical expertise in processing collections and putting it in service of social justice and human rights struggles.

While I was at UT Austin I had the opportunity to work with collections related to the Rwandan Genocide. We were working directly with survivors to preserve survivor testimonies and the [documentation of] local court proceedings that happened in Rwanda. I also got the opportunity to work directly with folks in El Salvador who had been involved with the civil war, and we worked together to digitize the recordings of Radio Venceremos, which was a radio station that accompanied the guerilla army [Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, FMLN]. Towards the end of my time [at UT Austin], we received a grant from the Mellon Foundation to continue building out this Latin American, social justice-focused postcustodial archival work.3 All these experiences have greatly informed how I approach my work in libraries, building these transnational collaborations that hopefully benefit all institutions and ensure that these histories are preserved for the long term.4

Concurrently to the work as a human rights archivist, I was also the librarian for Brazilian studies. The former Brazilian studies librarian had retired, and I was the only person [at the UT Austin Benson Latin American Collection] who spoke Portuguese and had done some research on Brazil. And so, I also ended up gaining more traditional subject specialist librarian experience. One of my missions when I was in that role was to broaden our collection on Brazilian hip hop, which is a significant youth culture movement in Brazil and is of great scholarly interest. I had done my [Latin American Studies MA] research on Cuban hip hop. I also hosted a hip hop radio show [Hip Hop Hooray] when I was in Austin for six years, where I focused on international hip hop, Brazilian hip hop, and hip hop from Latin America.5 All of this was informing my work as a librarian and expanding the types of materials that we collected and the types of narratives that are told through hip hop.

Bookshelves in the Biblioteca de Anomalías. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand.

Now, fast forward to UCLA where I work in the digital library program. One of my primary responsibilities is shepherding our collaborations with Cuban cultural heritage institutions, which I see as a continuation of my previous work. The Cuban collaborations do not have a human rights focus, but we are focusing on preserving cultural heritage materials that wouldn’t be part of a larger historical record were it not for this preservation and digitization work that we are undertaking with our partners. So my philosophy [of preserving marginalized histories] is still there, even when I’m not working with human rights collections.

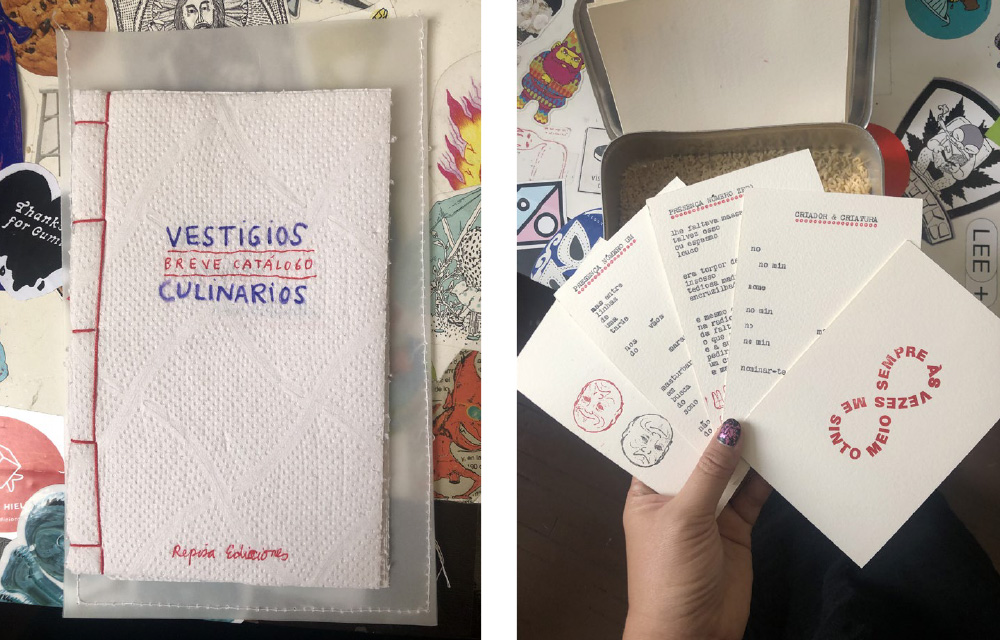

Cover of book written on a paper towel from the Biblioteca de Anomalías. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand. | Objects from the Biblioteca de Anomalías. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand.

During my time at UCLA, I have focused mostly on Cuba, but I also have this long-standing history of working in Mexico. That’s where I studied abroad, during my undergraduate period. I continued working there through my time at UT Austin, and while I was at UCLA, I got a Fulbright fellowship for a nine-month project in Mexico City working on a community-based archives project to document Day of the Dead practices in Xochimilco, Mexico, which is a southern borough in Mexico City that has strong ties to their pre-Hispanic past, and they’re recognized as such.6 Because of all those connections to Mexico City, I was brought into a conversation at UCLA about the potential acquisition of an artists’ book collection from Mexico City. The head of special collections, who was also very invested in artists’ books, told us that she could allocate a portion of the acquisitions budget to Latin American artists’ books for a period of several years. They asked me if I wanted to go along to some art book fairs that take place in Mexico City, and I was like, “Absolutely!” A lot of my friends in Mexico City are actually involved in the [art and experimental publishing] scene. So the Latin American studies librarian and I went to the book fairs and it gave us the opportunity to build new connections with producers of this work.

This trip is what led to the idea of curating the radical publishing in Mexico City series. I see it as an extension of my commitment to ensuring that marginalized voices are part of our historical record.

CZ That’s fascinating. Tell us how you arrived at the idea to curate the Radical Publishing in CDMX series—maybe starting from the book fairs and moving from there. What were the principles that guided your work? How did you identify participants?

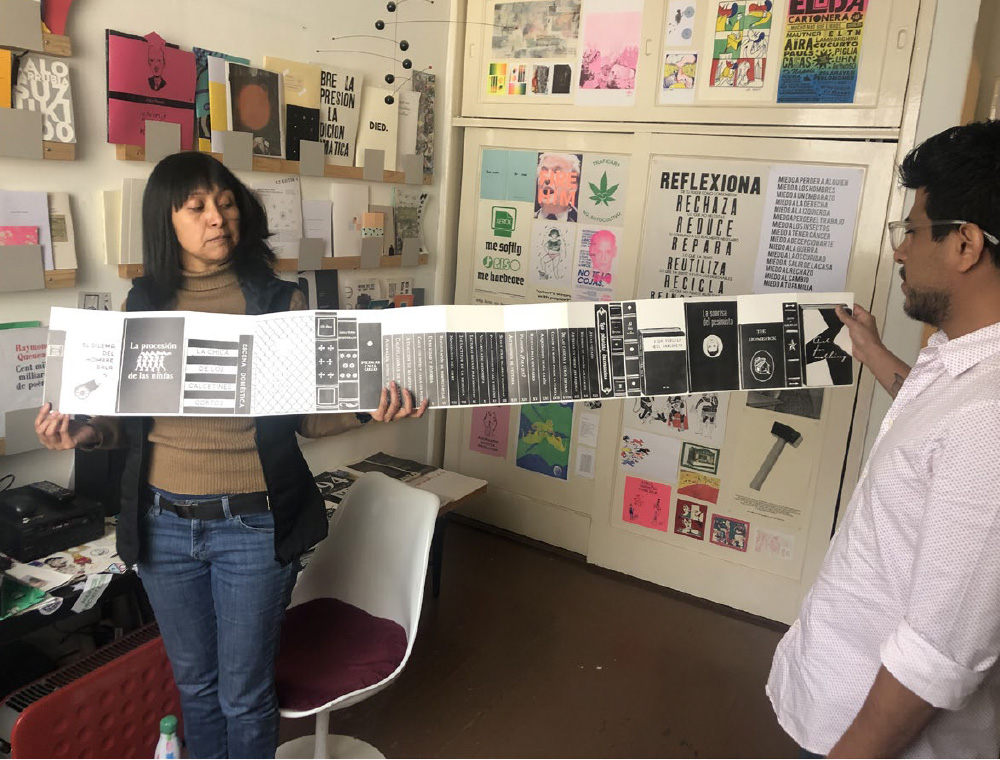

TS The Latin American studies librarian, Jennifer Osorio, and I took the trip to Mexico City in late January/early February 2020, which is when both the Index Art Book Fair and the Rrreplica Book Fair occurred. Index is more art focused and attracts international vendors—international in the sense that it includes Latin America as well as the US. Rrreplica is more of an independent fair. It definitely has a lot of art participants, but there is more of a punk rock sensibility to it. It tends to attract more local folks from Mexico as well from other parts of Latin America, and a little bit less so from the US.

When we attended these book fairs we got to talk directly with the producers of materials, which is always great. Two of the projects that really stood out to us were RRD and Esto es un Libro; La Casa del Hijo de El Ahuizote was also there. Sol Arechiga Mantilla7 was [at Index Book Fair] giving a talk on indigenous typography, but she was also there with another publishing project that she works on. When Jen and I were having these conversations with folks she suggested that we bring some of these people to UCLA. There could be some collaborations with local artists and, obviously, there could be a lot of different interests from across UCLA—from Latin American studies to design to the information studies department. So that was an idea that we were playing with in February 2020, but we all know what happened afterwards. The pandemic really made it impossible to plan for this type of work.

Around this same time, I had also just been accepted into the Rare Book School-Mellon Cultural Heritage fellowship, which aims to bring underrepresented folks into the rare books profession. As part of our fellowship we were introduced to the Bibliographical Society of America [BSA] and they gave us a free membership to the organization. When I was sitting in the information session learning about the organization, Erin McGuirl [executive director of BSA] told us that as members we could propose events and apply for funding, and that’s what got the wheels turning in my head. Maybe this was a way to continue building the relationships that we had started building in Mexico City, even if we couldn’t invite them to physically come to the US. BSA was extremely generous with their funding. I had submitted four separate proposals for the series and I wasn’t necessarily expecting that all of them would be accepted. But BSA really loved the idea for this series, and they sought additional funding to ensure that the whole series could take place. There was an anonymous donor who contributed to the series—special thanks to them and to BSA for really believing and supporting that work.

T-Kay Sangwand at Casa del Hijo de El Ahuizote. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand.

Objects from the Biblioteca de Anomalías. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand.

There wasn’t necessarily a well thought out methodology beforehand about who we wanted to participate. A lot of it was very intuitive and based on the relationships that I already had, and that we had started to build because of the trip. But, I think in retrospect, what really ties all the participants together is that their processes and practices are as important as whatever objects are produced as a result of it. All the talks really emphasized the relationships that go into producing something together, as opposed to just focusing on a technique of production or the object that is produced in the end. In general, I’m most interested in these networks of collaboration and solidarity that are both locally-based and transnational. These are the themes that I find particularly important and compelling to focus on.

CZ So, it’s all about people, right? We often focus on books as objects, but it sounds like the networks and the individuals, the connections, are really what animate this world. Tell us a little bit about the people that are involved with radical publishing in Mexico City. What kind of activities are they up to? What kind of experiences or goals animate their work?

Diego Flores Magón with the facsimile publication of Regeneración. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand.

TS I started off the series with Diego Flores Magón, who is the great-grandson of Enrique Flores Magón. The Flores Magón brothers are well known in Mexico because they’re considered the fathers of Mexican anarchism, which was a slight precursor to the Mexican Revolution. The brothers have had a really far-reaching legacy and influence in Mexico—they’re considered national heroes, which is, I think, kind of shocking for folks outside of Mexico to know that anarchists are viewed as national heroes—but they’ve also had a lot of influence on leftist progressive organizing in the US.8 The Flores Magón brothers were actually exiled to the US where they built ties with communists and labor leaders of that era. Their legacy was also reanimated in the Chicano movement of the ’70s and in the Mexican student protest movements of the ’60s. They had a very far-reaching legacy which Diego has inherited and really dedicated his life to: bringing that legacy to light, tying it to the present, and thinking about new ways that it can continue to be relevant. So, for him, there’s a very obvious family legacy that informs his work. I wanted Diego to start us off because he really can give us a historical perspective on radical publishing in Mexico City. The current location for his printing projects is in the original location of the Flores Magóns’ printing press in downtown Mexico City, so that sense of place is very important.

The second participant that we had was Sol [of hormiguero] who discussed the design of typography for indigenous languages. She’s approaching this not as a designer, but as a linguist and a translator. She’s thinking about how these messages can be best conveyed through translation, because a lot of indigenous cultures have more oral-based forms of transmitting knowledge. So, a central question to her work is, “If this is going to be written, how can it be transmitted in a way that is accessible and pleasurable to read?” The current typefaces that have been designed for literary publishing are not sufficient for [indigenous] languages because of the way in which the languages are structured—which is something that you wouldn’t think about unless you’re someone engaging in this sort of translation work and reading indigenous languages.

That was not a discussion I’d heard elsewhere and so it seemed important to bring into the dialogue. It’s also a fun fact that Diego and Sol are old family friends, so there’s also a sort of continuity between different participants in the series. Actually, all the participants know each other in one way or another because the scene is small like that.

We also had E. Tonatiuh Trejo from Esto es un Libro. He comes more from the world of publishing—he’s worked at major editoras [publishers]. One of his central questions is, “What is a book?” (as evidenced by the name of his project)9 and, “How can we break that down? How can we reconceptualize that?” I really appreciate how he is in conversation with many different actors and projects, not just in Mexico City. He’s also done a lot of collaborations with people in the global south and other parts of Latin America.

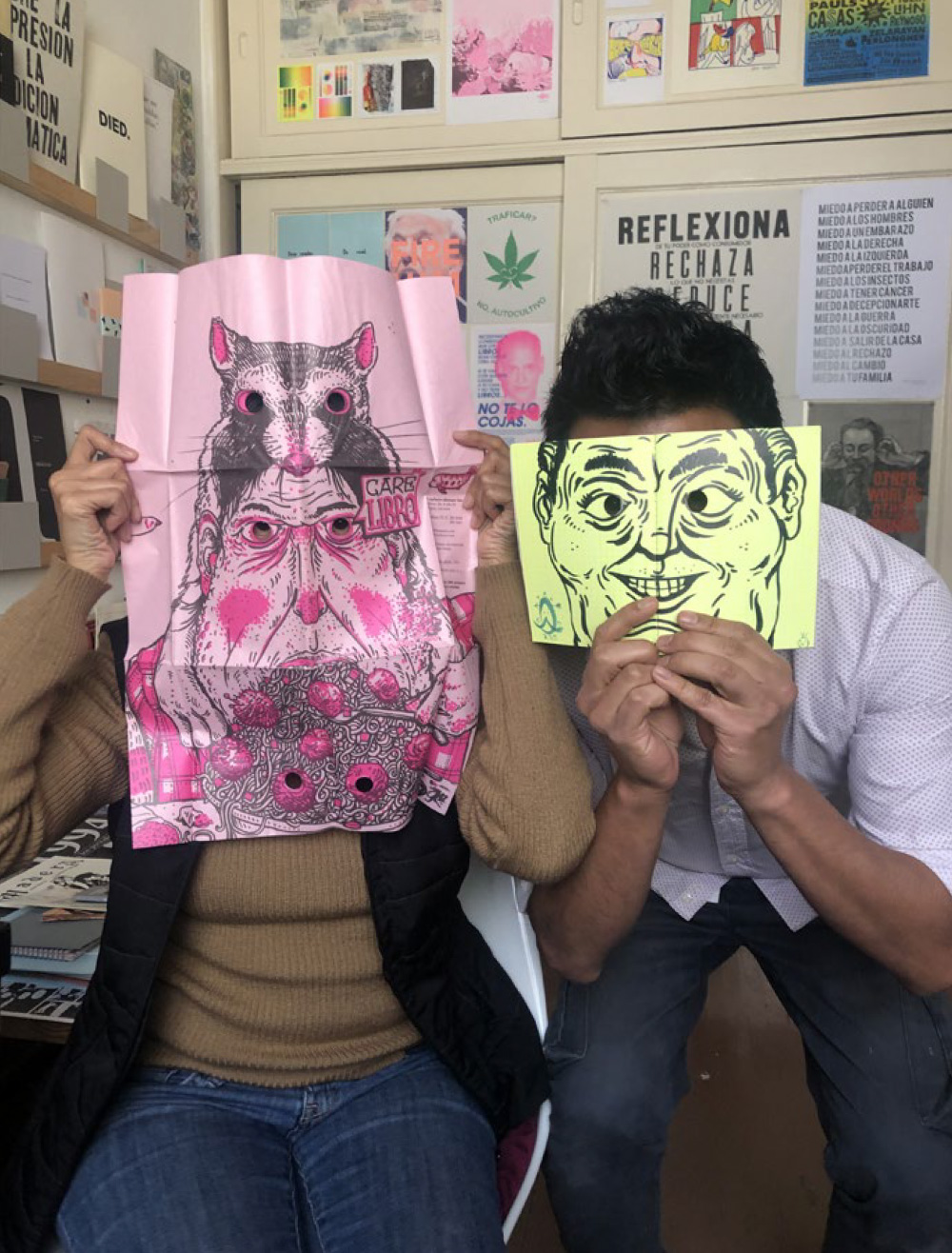

The last project that we featured involved two members of the RRD artist collective [Bruno Ruíz and Maria José Cruz Reyes], which does a lot of transnationally based work. They’ve done collaborations with similar radical pub-lishing endeavors in Southeast Asia, in addition to connecting with other folks in the US. I think Wendy’s Subway [an independent publisher with a reading room] is one of their main collaborators—they’re based in Brooklyn.

But what I really appreciate about their work is that while they’re artists like everyone who participates in RRD, they’re also interested in having their work seen and experienced outside of the art world. One of the main ways in which they do that is with a newspaper stand outside of the metro Juanacatlán [subway station]. Obviously, you’re going to have a huge cross section of people who are going about their everyday lives, and who can encounter this newspaper kiosk that has a lot of artist publications, zines, and artworks. It’s not your typical newspaper kiosk, so that tends to generate a lot of conversation from passersby who might not ordinarily go out of their way to go to a museum to see RRD’s installations, or to a book fair to see their work. That’s something that I really appreciate about them; they are really interested in building this larger network and having a broader conversation outside of the small and insular world of independent publishing.

CZ That actually relates to another question I had about how these projects are rooted in specific places and spaces. I think they all were associated with Mexico City, but while some of them are very invested in urban capital city networks, others really attempt to create connections with other parts of Mexico. Can you talk a little bit about how the projects’ creators conceptualize their relationship to place or space?

Street view of the RRD kiosk near Metro Juanacatlán in the San Miguel Chapultepec neighborhood, Mexico City. Photo: RRD

TS Yeah, I think this is a really interesting moment to reflect on that because I actually went back to Mexico City last week for other work stuff, including having in-person conversations with these people who I hadn’t seen in over two years. Obviously, the pandemic brought about a huge shift in people’s relationship to place in space. To give an example of that, two of the participants in the series have moved outside Mexico City. That seems fairly permanent. Diego is rethinking the significance of a physical space like La Casa del Hijo de El Ahuizote, especially during a pandemic.

Publications from various editorial projects that are sold at the RRD kiosk. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand.

Everyone that I talked to is reflecting on how their practice has changed. Diego, who has the printing press in this historic space—which was such an important part of building-out that family legacy—believes that the printing projects are still very important, but is questioning if it’s necessary for them to happen in this specific geographic place, or if that work can happen elsewhere.

Sol has been very much rooted in Mexico City, she’s chilanga10 born and raised, but the work that she discussed for the series—which is based in [the state of] Michoacán—is obviously outside of Mexico City. Her goal with that work is not necessarily to have the same sort of broad reach that maybe RRD is striving for; instead, it’s really intentionally focused on building local community ties and strengthening them using translation as a tool, and building cross-generational engagements with Indigenous languages in this particular community. As she notes in her talk, while there are many different communities across Mexico that speak Purépecha, there are obviously going to be some unique regional distinctions. That was something that she emphasized in her talk; not just that there are regional differences, but that there are even differences of how the language is spoken between households. Having that dialogue about language and translation with community members seems to strengthen relationships in and of themselves.

With RRD and their relationship to space, they are continuing with the kiosk. I think they have the benefit of operating an outdoor space, which has been relatively easier for them to continue during the pandemic.

Now that things are opening back up they are able to engage in the type of transnational collaborations that were a big focus of their work before the pandemic. During the pandemic they tended to focus locally, working with museums, such as the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil. They talked about the RedEx project, which engaged a network of artists within Mexico City to do different interventions on circulating objects.11 People’s relationships to space and place really expands and contracts at different moments in the pandemic. It’s definitely something that’s fluid.

CZ A lot of the speakers who participated in the series talked about or presented a project that explicitly tried to transcend or break down borders. Can you give us some examples about how they’re going about this work?

TS One of the threads that I found particularly interesting, which I think I’ve highlighted, is the south/south dialogues that occur, for instance, with RRD and other similar publishing projects in Latin America. And then, there are the transnational and diaspora dialogues that are particularly exemplified by Diego’s work and the types of collaborations he engages with because of La Casa del Hijo de El Ahuizote’s legacy.

But one thing that I want to emphasize as well, is that the global south is not a monolith. Mexico is not a monolith. One important aspect that I don’t think came out in the talks, necessarily, but in my own conversations with Diego and Sol, particularly, is that, as we in the global north think about our collaborations, how can we navigate power imbalances that occur from working with these different regions, or with local communities, if we’re working in large institutions? Some of those same conversations are also happening within these radical publishing projects. Diego and Sol both come from middle class intellectual families in Mexico City. Mexico is very colorist and classist, so they benefit from their lighter skin. They both work with indigenous communities: Diego works with the community of Oaxaca, where his ancestors are from, and Sol works with the [Santa Fe de la Laguna] community in Michoacán. So, they themselves pose these same questions of their role in this work. I really liked this one line that Sol says in her talk, “Soy apoyo pero no doy respuestas [I support but I don’t give answers].” She sees her role as supportive, but she does not give answers because she is not the expert in the room. That’s how I also see my role in facilitating these types of conversations. I don’t want to speak for people, but I want to be able to create the conditions where these conversations can happen. I think it would be really illuminating to delve more into those types of questions with these participants, and better understand how they choose to approach and navigate these different power imbalances in their own collaborations.

RRD members with UCLA librarians T-Kay Sangwand and Jennifer Osorio in the RRD studio. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand.

CZ Do you want to talk about where you see points of contact between this work in thinking about radical publishing networks, north/south dialogue, and south/south dialogue in relation to fine press publishing in the rare books world? I know you feel like you’re a newcomer to this world.

TS I’m not sure if I have a ton to say there, except, as I mentioned earlier, I definitely notice an absence of discussions of work happening in the global south in these global north spaces. I’m sure part of it is a language barrier, but also, I just wonder if people think that this work isn’t happening, or this work isn’t important. I think it makes sense to familiarize ourselves with the production that’s happening in the global south because it’s not insignificant. At these book fairs [in Mexico City] the representation is from all over Mexico, not just Mexico City, and also from Argentina, Colombia, Brazil, Chile. All these places have really fascinating creative projects, and I think what makes a lot of it different is the shared history between Latin American countries and the role of the US with dictatorships in Latin America, which, of course, has very concrete impacts on individuals and families. These histories inform radical publishing in these small independent projects.

CZ The pandemic really reproduced and magnified inequalities here in the US, but also on a global scale. It forced those of us who work in academic and cultural institutions to develop new strategies for programming and forging connections that could potentially help us push back against inequality or transform the way we operated, like the work that you did in conjunction with the BSA, bringing practitioners based in Mexico to present and share their work with US-based audiences. What did you learn from your virtual curatorial work—either about the nature of these inequalities, or about how we might think about overcoming them, or pushing back against them, and what we should remember in the coming years, going forward?

TS I haven’t fully thought this through, but here are some initial thoughts. Part of the reason why I wanted to organize this series is because, as someone who is getting to be more immersed in the rare book world because of this fellowship that I have through the Rare Book School, I haven’t seen a lot of courses that focus on Latin America unless they’re focused on the colonial period, and it doesn’t give us opportunity to actually engage with people from these regions. That’s one of the reasons why I thought it was really important to highlight contemporary work, because that way we can actually engage in real-time with folks from the global south about their practice and its significance.

Gwenn Huesca Reyes and E. Tonatiuh Trejo holding a book from the Biblioteca de Anomalías. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand.

Along those lines, typically when folks from the global south are invited to participate in global north spaces, one of the conditions is that they do so in English, which, for most people in Latin America, is not going to be their first language. I think the pandemic and the need to create virtual programming really enabled me to think about how we can center global south voices in the language that they feel most comfortable. Another aspect that informs my work in the library and archives, working in Latin America primarily, is language justice, which is the idea that people have the right to communicate and be heard in the language they feel most comfortable.12 For instance, when I’ve been participating and negotiating these postcustodial collaborations [in Latin America], all these conversations happen in the language of the country where we’re trying to work. It doesn’t make sense for those conversations to happen in English. Defaulting to English creates a false hierarchy, and we run the risk of not being able to communicate fully with whoever we’re partnering with.

I’ve been very influenced by the work of the now-defunct Antena Los Angeles collective that did [simultaneous] interpretation through a language justice framework.13 They provided interpretation not just as a service, but also asked how we can ensure that we are creating spaces where equitable communication can happen and where one language isn’t “hierarchized” over another. I think this is a very new concept in most spaces that I’ve worked in, where translation or interpretation14 is an afterthought and it’s something that’s considered a burden.

Because the stakes are somewhat lower in virtual spaces—you’re not paying for everyone’s food and travel expenses—it gave us the opportunity to advocate for a language justice framework with a lower investment than what you would have to do in person. I think it really demonstrated how necessary it is to have this language justice framework, because everyone that I invited to speak was so relieved that they could give their talk in Spanish. That’s the language they feel most comfortable expressing their ideas in, and I think for these complex ideas, when people are talking about their artistic practice, it’s very important for people to understand how they’re approaching it in their own words. The language justice framework is something that I would like to see sustained in both virtual and in-person spaces as things are opening back up. One thing that I’ve been thinking a lot about is how we can better educate folks who are working in these transnational collaborations on how to incorporate language justice into their work.

CZ That was definitely one of the things about the programming that stood out to me—the way the BSA is working increasingly in this framework, too. I think it’s great. So, I hear you are turning your experiences curating this series into a class for CalRBS. Can you give us a sneak preview of what the class will look like and how it builds from the important early programs that you organized over the last few years?

Gwenn Huesca Reyes and E. Tonatiuh Trejo with cutout prints from the Biblioteca de Anomalías. Photo: T-Kay Sangwand.

TS Shout-out to Rob Montoya, the director of California Rare Book School, for suggesting this idea. I was really honored when he approached me about it, and said that he really appreciated the Radical Publishing series and wanted to think about how it could be expanded. That’s the impetus for the course we’re hoping to do in the summer of 2023. We are still in the very preliminary planning stages. That’s part of what my last trip to Mexico City was starting to explore. We want the class to actually be taught by practitioners in Mexico City, as opposed to me giving the lectures. I want to really focus the course content on the social context in which this creation is taking. I also would like participants to get some hands-on experience working with physical materials and learning about different printing techniques.

I think a big part of the conversation is going to be how this work has been impacted by the pandemic and how folks have adapted within this new context. I don’t want the course to just focus on the objects of production, but on how we can build more opportunities for dialogue and exchange between our different worlds.

CZ It seems like a really excellent place to end our conversation. T-Kay, thanks so much for speaking with me.

NOTES

1. For more information about the Radical Publishing in CDMX series, see bit.ly/radpubcdmx.

2. Sangwand’s lecture for CalRBS, “Prison Libraries, Indigenous Typography, and Experimental Publishing: Reflections on #RadPubCDMX,” is available at https://www.calrbs.org/events/calrbs-online/.

3. The postcustodial theory of archives is “the idea that archivists will no longer physically acquire and maintain records, but that they will provide management oversight for records that will remain in the custody of the record creators.” Richard Pearce-Moses, A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology (Society of American Archivists, 2005).

4. For more information on Sangwand’s postcustodial work, see “Preservation is Political: Enacting Contributive Justice and Decolonizing Transnational Archival Collaborations,” KULA: knowledge creation, dissemination, and preservation studies (November 2018): 10.5334/kula.36.

5. Past episodes of Hip Hop Hooray are archived at www.mixcloud.com/tttkay.

6. For more information on the Day of the Dead documentation project in Xochimilco, see La Fiesta de los Muertos en Xochimilco, eds. Carlos Mendoza and Víctor Rosas, CDMX: Alcaldía de Xochimilco, 2019, https://www.inpi.gob.mx/gobmx-2020/libros/la-fiesta-de-los-muertos-en-xochimilco.pdf.

7. RRD, Esto es un Libro, La Casa del Hijo de El Ahuizote, and hormiguero were all featured speakers in the “Radical Publishing in CDMX” series.

8. For more on the Flores Magón influence in the US, see Kelly Lytle Hernández’s book Bad Mexicans: Race, Empire, and Revolution in the Borderlands (WW Norton, 2022).

9. The English translation of “Esto es un Libro” is “This is a book.”

10. The term chilango/chilanga refers to someone who is from Mexico City.

11. For more information on the RedEx project, see www.erreerrede.org/redex.

12. Language justice is defined as “the right everyone has to communicate, to understand, and be understood in our language(s). It entails a commitment to facilitating equitable communication across languages in spaces where no language will dominate over any other . . . Language justice is a political foundation, a conceptual framework and a set of tools and practices.” Antena Aire, How to Build Language Justice (2020), 4, http://antenaantena.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/AntenaAire_HowToBuildLanguageJustice-2020.pdf.

13. The interpreters for Radical Publishing in CDMX series are former Antena Los Angeles collective members.

14. While many people use the terms interpretating and translation interchangeably, they are different actions and require different skills. “Interpreting is the spoken or signed transfer of information from one language to another. Translating is the transfer of a written text from one language to another” (Antena Aire, How to Build Language Justice, 2020 edition, p. 7).