Paris was liberated by the Free French forces and the Americans on 26 August 1944, the day that de Gaulle made his triumphant entry into the city. The first substantial book on the occupation and the liberation of Paris was published less than eight weeks later, an extraordinary achievement considering that the country was still at war, the Germans were still in France, and there were shortages of everything.

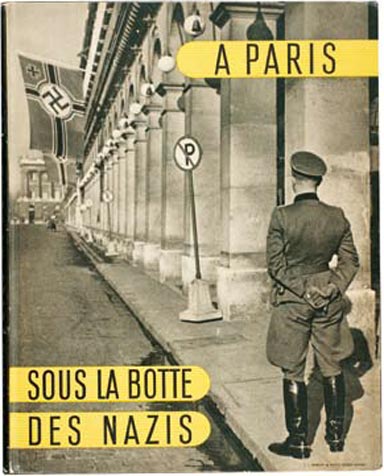

À Paris sous la botte des Nazis (1), published by Éditions Raymond Schall in October 1944 with photographs principally by his brother Roger Schall, an internationally known fashion and commercial photographer, went through five editions, at one time selling 1000 copies a day. It was this book that stimulated my interest in books published in France in the period immediately after the liberation of Paris, up to the end of 1946, on the subjects of the occupation and liberation, events that affected deeply the lives of every French man and woman. How was it that a book of such quality could be published so soon after the Germans had been driven from Paris, when the city was still in turmoil? How was the book used as a medium to express the deeply felt emotions of those who at the end of the occupation must have felt that they were waking from a terrible dream? A German soldier complained of the drab sadness he found in Paris. The Parisian replied, ‘You ought to have come when you were not here.’

1

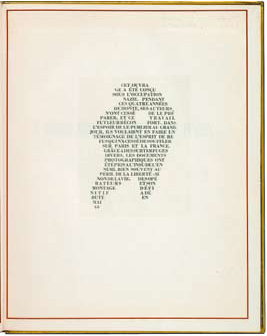

À Paris sous la botte des Nazis was produced in hard covers, with a belly band which repeats the title and adds, in translation ‘which the French must never forget’. The front endpaper has an outline of the helmet of Marianne, the French heroine, reversed out in white from a deep orange background; on the opposite page the shape of the helmet is repeated in printed text (2) which explains that the work was conceived over ‘these four years of shame’, that the photographs were taken under conditions which threatened liberty and life, and that the book had begun to be designed and put together in May 1944. The colophon on the recto of the last page by the designer/artist Jean-Louis Babelay records the different editions printed on different papers (3). Such an elaborate series of editions seems remarkable considering conditions at the time and the urgency with which the book was produced. But the Bibliothèque nationale has only the trade edition and I have not found these other editions in any French library.

2

3

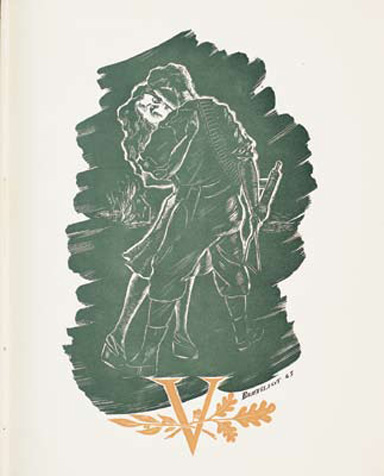

Raymond Schall went on to publish three other equally handsome books. Un An appeared in October 1946 and is a book of photographs of Paris after the liberation and in the first months after the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, until October 1945. There are some dramatic photographs laid out more expansively than in the earlier book. The colophon records the text being set in ‘Bodoni Italique Corps 13’, and a further edition of 200 numbered copies was printed on Vélin Pur Alfa. There is a full-page wood engraving by Élie Bertillot of a resistance fighter, gun on one arm, a beautiful young woman on the other (4). This is the overriding characteristic of the literature, a yearning for nobility and heroism in what in reality was a complicated and troubled transition from occupation to freedom.

4

The most telling photograph in Un An is a double-page spread showing the roofs of Paris on Christmas Day 1944. The distant horizon is as visible as it would be today, but then it was because there was no smoke from the chimneys: the Parisians had no fuel, in one of the coldest winters of the century. Yet it was in these grim conditions that superb books were beginning to be produced.

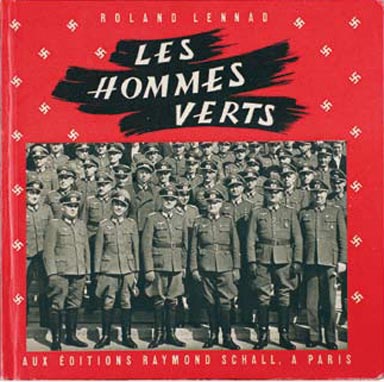

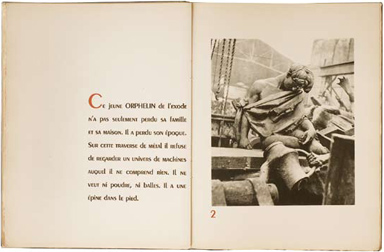

Schall published a third book in 1946, Victoires des Français en Italie, conceived and executed by Babelay, and these three books were then sold as a boxed set. Les Hommes verts is another book published by Schall in 1945 (5). Designed by Babelay with text by Roland Lennad, it is Schall’s most intriguing book, conceived with heavy French irony, and described as ‘no. 1 in a new collection of histories and accounts of our times’. None followed, and it is neither a history nor an account, but an angry satire against the Germans, asking what kind of people they are to have behaved in the way they did. They are ‘the green men’, because of the German soldiers’ green uniforms. Lennad’s captions provide the counterpoint to the satire that lies in the selection of the photographs, many of which were taken by Roger Schall on assignments in Germany before the war. ‘These fine people have killed, tortured and massacred’ is the headline of a spread of photographs of Goebbels reading to his children, middle aged men in a bierkeller, and folk dancing Bavarians in traditional costume.

5

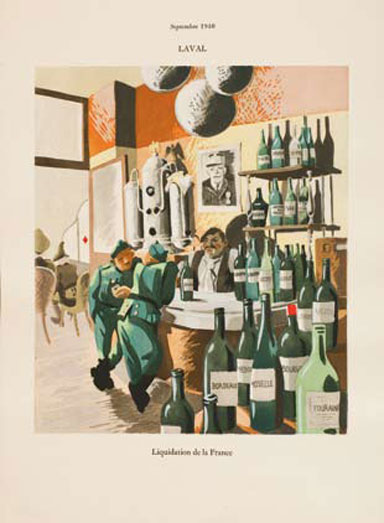

Satire is the underlining theme of Livre noir 1939–1945 with its powerful illustrations by Chancel (6) and an introduction by André Billy, author and member of the Académie Goncourt. It is a chronicle of France’s weaknesses and follies, and her suffering, in 30 folio plates, loose between cloth bound boards, in a slipcase, and was published in Paris on 30 November 1945.

6

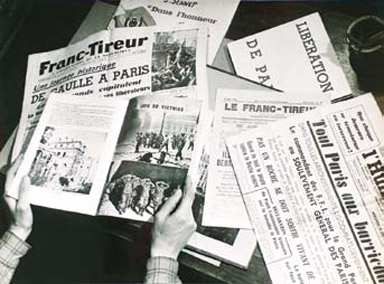

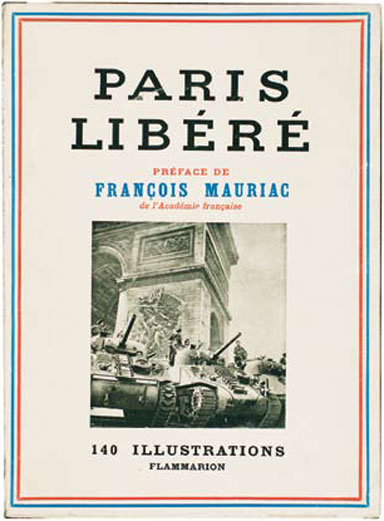

In late 1944 the photographer Pierre Jahan photographed the interior of his apartment, a series of intimate views of his home life in Paris at that time. One photograph is of a spread of newspapers and books that record the liberation of Paris (7). In the foreground is an open copy of Paris libéré, with a preface by François Mauriac, published by Flammarion in the last quarter of 1944 (8). This 96 page trade edition (there are no other editions) is on a smooth cream paper with good reproduction of the photographs and an elegantly designed text. This is just one of many books, booklets and single issue magazines on the liberation of Paris published within a few months of the event. There are at least six books with the title Libération de Paris and many others with those words included in the title. Many of them are books of photographs, and there were plenty of photographers on the streets of Paris during those five days in August 1944. The most notable was Robert Doisneau, after Henri Cartier-Bresson the most admired of the French photographers of that era, but Pierre Jahan went out on the streets to photograph the conflict and, immediately after, made the prints in his darkroom: he explains that there was no electricity so he had to use daylight to expose the paper. Fortunately the prints still exist in pristine condition; this is all the more remarkable because Jahan’s negatives and many of his photographs were destroyed in a disastrous fire in his apartment in 1948.

7

8

In 1942 statues of lead, bronze and iron were torn up from the streets and squares of Paris and were stored in a yard before being sent to Germany to be melted down as scrap. At considerable risk to himself Jahan photographed the statues piled up on their sides like grotesque effigies. These photographs were published in a book, La Mort et les statues, with text by Jean Cocteau, on 30 October 1946. The printer Dominique Viglino produced an edition of 450 numbered copies set in Peignot (9). The typeface, the quality of the printing and the photographs make this one of the most sought-after books of the period. Another title, beautiful in its simplicity and disciplined design, is Écrit dans l’ombre by the playwright Jean Giraudoux, who had died in 1944. These are his last writings and include his thoughts on the present situation in France and what the French must do to prepare for the new world ahead of them. Published by Éditions du Rocher in Monaco in 1944, it is also set in Peignot, with the page numbers and rules and devices decorating the running heads in pale blue/grey, in contrast to the black text. It was printed on the presses of ‘the master printer’ Jean Bétinas at Annonay in a numbered edition of 580 copies with a further 50 hors commerce copies. Peignot was designed by the great illustrator and painter A M Cassandre, famous for his 1930s posters of liners and locomotives. Charles Peignot was the owner of the Deberny et Peignot type foundry and the publisher of the most important pre-war design and graphics magazine Arts et métiers graphiques, and the colophon (10) is from an hors commerce copy specially printed for him.

9

10

There are other books which are grand but lack the flair and imagination of the two above. Jours de gloire: Histoire de la libération de Paris is unbound between paper covers, a large quarto with generous margins, printed on Lana paper, with the usual array of different editions, all of them numbered. The main edition comprises 1000 copies and the book was published under the patronage of the Ministry of Education, underwritten by SIPE, to raise funds for the Red Cross for the benefit of French prisoners of war. There are distinguished contributing authors including Paul Valéry, Paul Éluard, Colette and André Billy, but what makes the book important – and expensive – is the series of plates which includes an engraving (as well as two in-text illustrations) by Picasso (11). Other illustrators are Daragnès, Dignimont and Touchagues, names that are relatively unknown now but who were then leading book illustrators.

11

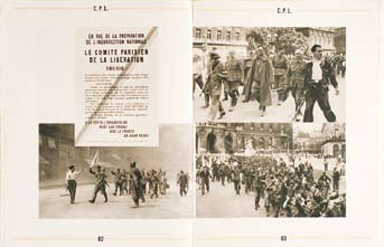

The conditions that prevailed in France at this time make any finely printed book on hand-made paper extraordinary in its conception and execution. The folio volume in paper covers Ors et gris: Poèmes des prisonniers takes poems from Pierre Seghers’s Poésies 43, the 1943 edition of the well known poetry serial, and republishes them in a much larger, more luxurious format. The book is used as a medium for celebrating poems that had first been published in more difficult times but could now be re-presented as part of the triumph of liberation. The gold blocking, the pale grey barbed wire motif and the dark, rather menacing engravings by Maurice L’Hoir all add to the presence of the book, which was published in November 1945 by Éditions Kérénac, and printed in Paris by Curial-Archereau. Another folio volume is PARIS les heures glorieuses août 1944 which reprints very handsomely the declarations of the Comité Parisien de la Libération, printed sheets flyposted on walls all over Paris and a familiar backdrop to Paris street scenes at the time. Some run to two or three pages and were perhaps also published as pamphlets. Many of the transcripts of the proclamations are printed in black on a buff background and the second colour is used for the rule at the foot of every page. The book also contains fullpage photographs of the liberation reproduced better than in any other contemporary book (12). It was published in October 1945 in 1500 numbered copies, with a further 500 hors commerce copies, all printed on Vélin Alfa by Draeger.

12

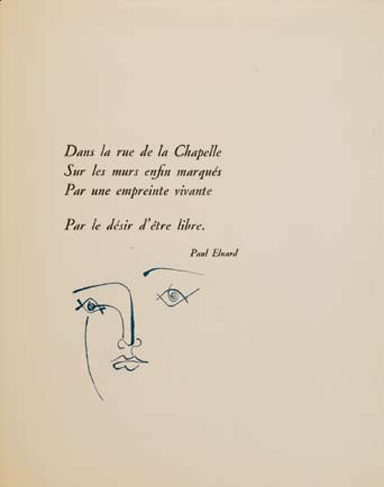

There are other publications that are ephemera rather than books, but are still designed and printed to the highest standards and often have content of interest. The programme for the Gala de la nuit de la libération de Paris on 28 October 1944, just two months after the event, is printed in four colours with a cut out cover and silk cord down the spine (13). Colonel Henri Rol Tanguy, who directed the military operation, was the president of the gala and there are full-page photographs of him and General de Gaulle. There are photographs of the conflict on the streets, and for the gala itself there are performers from the opera, the Comédie-Française, bands and orchestras, and film and music hall stars such as Charles Trenet. It was printed by Gaschet and each copy is numbered. The literary contributions to such programmes could be important. Paul Eluard’s poem ‘En plein mois d’août’ which he had written in the month of the liberation was first printed in another programme for a gala held by the Communists on 11 November 1944.

13

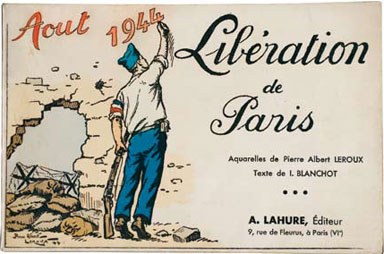

There are many other illustrated books recording the occupation and liberation, not with photographs, but with drawings, sketches and paintings – and cartoons and comic strips. One of the most charming is Août 1944 libération de Paris with watercolours by Pierre Albert Leroux (14). Its sketches of nuns and nurses on bicycles, burned-out lorries and captured German soldiers vividly record the events of those few days, yet also sanitise them. It was both published and printed by A Lahure on 1 March 1945 with a numbered edition of 100 copies, each with an original watercolour, and an unnumbered trade edition. There were also children’s books. Paris 11 Novembre 1944, with illustrations by J P Lenoir, was published by Éditions de l’office central de l’imagerie and printed by Plouvier in Paris. After a short introduction that starts ‘Petits enfants de france’ , the book continues with a series of plates of the different regiments and groups that marched through Paris on that most significant day of remembrance. The German army still occupied French territory, but the people of France felt liberated. Britain is represented with the Royal Artillery, the Royal Navy and the ‘Scotches’; the Front National and the Communist Party are included but so are Churchill and de Gaulle (15). Lenoir’s illustrations are highly stylised, and it is more of a polemic designed to rebuild pride in France than a book to entertain small children.

14

15

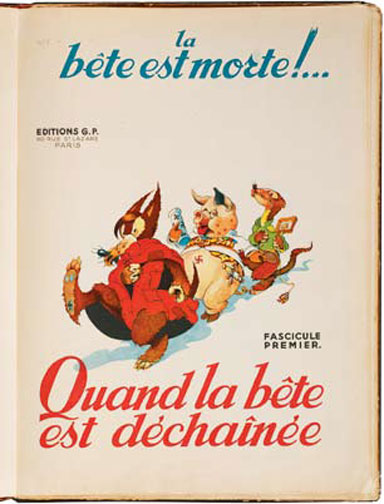

Not for children is an early bande dessinée published in two slim volumes in 1944 and 1945. La Bête est morte! is set in a world where the animals are living peacefully until invaded by the barbarians represented by the German pig, the Nazi wolf and the Vichy polecat (16). Although the style is entirely different, the imagery is very similar to that of Livre noir 1939–1945 in depicting a soft, selfindulgent, innocent France overrun by a tough, ferocious enemy. Grotesque black-uniformed wolves drive the rabbits holding little suitcases into the cattle trucks. But eventually with the help of the British bulldog and the American bison the pigs and the wolves are driven out. The colophon of the first volume states,

Entre Le Vésinet et Ménilmontant dans la gueule du Grand Loup, au groin du Cochon décoré et sans l’autorisation du Putois Bavard, cet album a été conçu et rédigé par Victor Dancette et Jacques Zimmermann, et illustré par Calvo sous la direction artistique de Williams Péra.

16

The ‘Grand Loup’ is Hitler; the ‘Cochon decoré’ the German with his medals, and the ‘Putois Bavard’, the long winded polecat, is Pétain. It was printed in Paris in the ‘third month of the liberation [November 1944]’. The colophon to the second volume states that the book was conceived in the occupation but published in the liberation, that it was written by Victor Dancette and published in June 1945 by Éditions G P ‘with the hope that the beast is well and truly dead’.

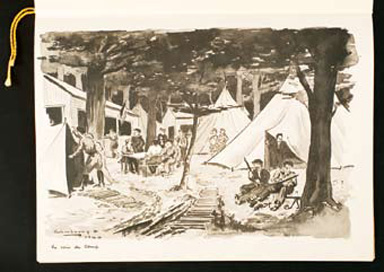

Another book with its own touch of mythology, which emphasises the heroic in its design and illustration, is Ceux du Maquis, a folio book of 64 pages and 32 mainly black and white plates on a good quality cream cartridge paper in paper covers. We have seen the movies and read the books about the resistance and the maquisards, and it is hard to take at face value even their names, ‘Grand Jean’, ‘Camille’, ‘Floristan’, ‘Madame Lucette, the mother to the maquisards of the band Camille’. The one-page introduction by ‘Floristan’ is dated 28 September 1944, just a month after the liberation of Paris. It states that in May 1944 there were 40 maquisards in the group, and by September this number had swelled to 200 – ‘sowing terror in the ranks of the enemy’. De Gaulle’s call to action on the BBC on 6 June and the Allied landings would have greatly increased the number of recruits. The emotion of the introduction is palpable – ‘Floristan’ writes of ‘the contrasting images between peace and conflict, between hope and fear, fighting and peace, destruction and reconstruction’. He adds, ‘I call out to the living the names of the dead whose achievement endures.’ The book’s pen and wash drawings show daily life in the ‘camp de Goths’ in the Morvan forest region of Burgundy, south east of Auxerre (17). This was in the occupied zone. There are also portraits of the principal maquisards, and these bring home the need that there was to memorialise people and events even while fighting in France was still going on. This need can be seen even more clearly in the light of de Gaulle’s deliberate indifference to the resistance movement. By the time Floristan had written his introduction de Gaulle had already visited resistance groups in southern France. The historian Julian Jackson writes that Serge Ravanel, a resistance leader in Toulouse, remembers the day as one of the saddest in his life. ‘Our interview lasted an hour. De Gaulle asked me no questions. I discovered the existence of an immense abyss between this man who had lived all the war outside France, and the Metropolitan Resistance which had had such a different experience.’ Ceux du Maquis’s author was Blémus, whose maquisard name was ‘Cherbourg’. He worked at the Institut géographique national, which published the book in 1945, and though the printer is not identified the production and design are of a very high quality.

17

A book that does combine realism with high quality printing and design is the folio volume Buchenwald, Scènes prises sur le vif des horreurs nazis. There are 78 full-page plates drawn by Favier, Pierre Mania and ‘Boris’, with a substantial text by Mania. Favier’s delicate pencil drawings of life and death in the camp have great power, but it is his formal portraits of individual inmates which are the most memorable images in the book, and are perhaps unique in holocaust iconography. It was published in Lyon on 31 July 1946 by J-L Sibert in a surprisingly large edition of 1200 numbered copies.

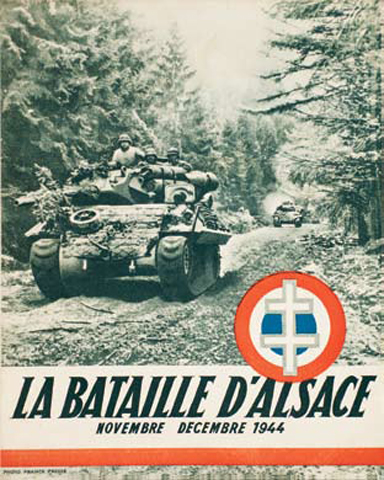

A quite different book that records the final days of the war in France is La Bataille d’Alsace: novembre-décembre 1944 (18). It is small and poorly printed, but is a sought after by collectors because the photographs are by Germaine Krull, much admired by Man Ray and other artists in France in the 1930s, who by 1944 had become a war photographer attached to shaef. The text is by the important novelist Roger Vailland (known to British readers for his Prix Goncourt winner La Loi – ‘The Law’ – published at the end of the 1950s). This book shows in photographs and text the reality of war, and yet its poor production and design militate against its message and are in marked contrast to the books described above.

18

Another modestly produced book with undistinguished design on thin paper, but with unusual content, is Henri Calet’s Les Murs de Fresnes, published by Éditions des quatre vents on 30 November 1945. Fresnes prison on the southern outskirts of Paris was notorious as a place of execution, but also for prisoners in transit. In Calet’s introduction dated May 1945 he writes,

Photos, film, flying bombs, television … this is the century of progress – gallows, gas chambers, dissection rooms, ovens; there are lampshades of human skin, you can be shot in the back or hung by the feet. I believe we are living in an utterly abject century. After Ravensbruck, Auschwitz or Dachau, it can appear today that Fresnes was a tolerable gaol, if one dares even say it. A sort of marshalling yard to be despatched into the unknown. From Fresnes to Buchenwald, from Buchenwald to Dora, from Scylla to Charybidis.

The photographs and text in the book record the ‘precious graffiti’ on the walls of many of the 500 cells at Fresnes, and inscriptions on metal food bowls; and they reproduce dockets left behind by the Germans. Scratched on the wall of cell 71 : ‘1381539 Sergeant David Kz RAF 19-1-44 . Staff Sergeant R. H. Mangenast 19-1-44. Took ’em over 3 mos to get me.’

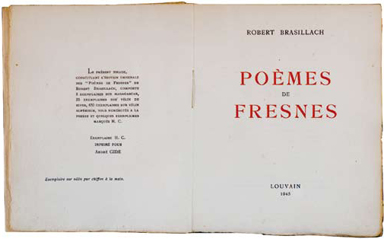

The Germans evacuated Fresnes prison on 11 August 1944 and it was later taken over by the new French government, who immediately used it to imprison collaborators and other ‘enemies of the state’, and for executions. The most notable execution was by firing squad of the 35-yearold writer and journalist Robert Brasillach on 6 February 1945.

Brasillach was an extraordinary combination of opposites, a writer of flowery, somewhat precious novels, and a journalist and critic with a hard edge. At the age of 21 he had published a mock obituary of André Gide, suggesting that the writer, then 60, was now an old man who had nothing more to say so might as well be dead. In 1944 , when he reprinted the article in a collection of essays, he mentions proudly that Gide has recorded the article in his published diary. From 1937 he was editor in chief of the magazine Je suis partout, sometimes kindly described as ‘lively and polemical’; it admired German and Italian fascism and regarded communism and the Jews as the enemy, but after the occupation became even more rabidly pro-Nazi and anti-semitic. In August 1944 Brasillach was arrested in Paris hiding in an attic. While in Fresnes prison he wrote a series of poems and their quality and energy suggest that this was one of the most creative periods of his life. He shared cell 344 with Henri Bardèche, the brother of his brother in law and greatest supporter Maurice Bardèche. Henri had been arrested because he ran a Fascist bookshop in Paris. Calet in the book described above does not record any graffiti in this cell but there must have been some, because one of Brasillach’s poems, read out at his trial, is called ‘Les noms sur les murs’ (‘The names on the walls’). After the verdict, writers, intellectuals and artists including Mauriac, Camus, Claudel, Cocteau, Derain and Vlaminck (but not Gide, Sartre, or Picasso) petitioned de Gaulle to commute his death sentence. But the execution took place even though many later capital sentences were commuted. Unlucky timing and an unapologetic defiance in court contributed to Brasillach’s fate. On 12 November 1945 Brasillach’s Poèmes de Fresnes was printed in Louvain in Belgium on the presses of the Imprimerie Sainte-Agathe. There were three editions and a number of hors commerce copies of which one, the copy shown here, was printed on a different paper specially for André Gide (19). The printing of a single copy as a posthumous gift to an old adversary makes this an object with a particular resonance; it is no longer just a book.

19

The work of writers, artists and printers has left us handsome memorials of this tumultuous time in the history of France. The French used the book as a vehicle to express their hopes, fears and beliefs. The occupation was now behind them and they immediately recognised that an important part of the healing process was to write about it, in books.

List of books

À Paris sous la botte des Nazis by Jean Eparvier, Paris : Éditions Raymond Schall, 1944

Un An by Jean-Louis Babelay, Paris : Éditions Raymond Schall, 1946

Victoires des Français en Italie by Jean-Louis Babelay, Paris : Éditions Raymond Schall, 1946

Les Hommes verts by Roland Lennad, Paris : Éditions Raymond Schall, 1945

Livre noir 1939–1945 by Chancel [illustrator] and André Billy [preface], Paris : Éditions de la Nouvelle France, 1945

Paris libéré by François Mauriac [preface], Paris: Flammarion, 1944

La Mort et les statues by Jean Cocteau, Paris : Éditions du Compas, 1946

Écrit dans l’ombre by Jean Giraudoux, Monaco: Éditions du Rocher, 1944

Jours de gloire: Histoire de la libération de Paris by Paul Valéry, Paul Eluard, Colette et al. Paris : SIPE, 1946

Ors et gris : Poèmes des prisonniers by Pierre Algaux, Paris : Éditions Kérénac, 1945

PARIS les heures glorieuses août 1944 by Claude Roy, Montrouge: Draeger [printer], 1945

Gala de la nuit de la libération de Paris by Félix Vitry [editor], Paris: Gaschet [printer], 1944

Août 1944 libération de Paris by I Blanchot and Pierre Albert Leroux [illustrator], Paris : A Lahure, 1945

Paris 11 novembre 1944 by J P Lenoir, Paris: Éditions de l’office central de l’imagerie, 1945

Ceux du Maquis: Plainefas, Vermot, Les Goths by Blémus [illustrator], Paris : Institut géographique national, 1945

Buchenwald, Scènes prises sur le vif des horreurs Nazis by Pierre Mania, Lyon: Imprimerie artistique en couleurs [printer], 1946

La Bataille d’Alsace: novembre-décembre 1944 by Roger Vailland, Paris : Jacques Haumont, 1945

Les Murs de Fresnes by Henri Calet, Paris : Éditions des quatre vents, 1945

Poèmes de Fresnes by Robert Brasillach, Louvain: Imprimerie Sainte-Agathe [printer], 1945