Andrew Anderson, Enclosures: Times and places

Foreword by Alan Powers

Evergreen Press, 2009

In the bellchamber of St Peter Mancroft Church, Norwich, is a glorious window full of reds, blues and golds: there are shown the 13 bells, all numbered; the clocks measuring the hours; the alleluias calling the sleepers to wake; Saints Peter with his 29 June feast day and Agatha, patron saint of bellringers. Turn your back to the window: facing you is a framed broadsheet, of St Peter holding his keys and setting sail in his fishing boat with the large tenor bell on deck, too large to fit into the hold. ‘And there the bells are ringing . . . O that we were there!’ is part of the inscription. Both window and broadsheet are the work of Andrew Anderson and a fitting introduction to this selection of engravings, superbly presented in the Evergreen Press’s Enclosures: Times and places.

Anderson’s main professional life has been devoted to architecture. He described his working day in Archigram 2 (1962), when his practice was based in the Close at Norwich Cathedral, beginning with 8 am Eucharist. After dealing with correspondence and site visits, the afternoon was given over to architectural drawing, encouraged by pictures of a Massey Harris tractor and Joan of Arc’s Tower in Rouen, the silo-like thirteenth-century cylindrical donjon – an enclosed place if ever there was one. The day ended after supper with work on a quarterly broadsheet, heraldic paintings, letter sequences and, of particular interest to this book, engravings.

The religious pattern behind this life is clear and recalls in this respect communities at, for example, Ditchling. But where Gill was influenced by the preaching Dominicans, here it was the monastic tradition of the Benedictines that seems to have been more influential: their work was ‘carried out as the progress of the Christian Year, the work of Bach, the need for care of the sick, the majesty of our Abbeys and the Rule of St Benedict spurred us on to greater deeds’. For relaxation, there was sailing on the Broads and hearty singing in the local pubs. As Dennis Crompton of the Archigram Archive observed, not unkindly, they were known in the days of both Brutalism and the Swinging Sixties as ‘the Christian weirdies’.

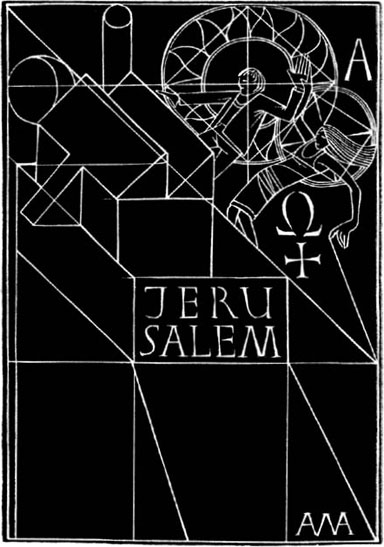

In this collection one may detect not only the thematic and stylistic influences, mostly from the 1960s and 70s, but also the need to grow beyond them. Andrew Anderson’s account in Matrix 28 tells how from 1960 onwards he ‘escaped’ from the influence of Gill, more particularly the figurative work. (Gill’s late design for the brick St Peter’s Church, Gorleston, Suffolk, is a different matter.) Bodies become angular (a shift seen in comparing ‘Gloria’ with ‘Jerusalem’ and ‘Nativity’), the lettering freer. In fact, his debt seems in this book more to David Jones, as Alan Powers remarks in his foreword. The Christian iconography persists: steps and ladders signifying the Ascension; the Ark (I wonder if other, subconscious, influences are not the vernacular mystery plays, and their staging, with their extraordinary combination of the mundane and the miraculous) and, very potently, the monastic cloister: ‘Heaven on Earth’ (the artist’s workroom) has every appearance of a monastic cell; the reconstruction of ‘Castle Acre Priory’ as imagined from the east; even the private house he lodged in, Gurney Court, has its Alleluia above the enclosed courtyard

Many of these engravings have a dynamism: the figures in ‘Jerusalem’ where work, in the shape of a geometric work block with its round tower, and play, lit by the sun’s rays and the moon, are all made divine by the alpha and omega. I wonder how the Annual Youth Conference of Cambridgeshire Education Committee in 1961, for whom it was made, received it – they were, however, the heirs of Henry Morris whose pioneering ideas on community education found architectural form in Gropius and Fry’s 1939 Impington Village College.

The mills and silos in Anderson’s engravings are far from satanic. The unity of work and play suggests a world in which people have space to breathe and pass their days. Sea and sky are not blotted out by urban and industrial blight; it is a world of hope. As I let these engravings sink in, the ones to which I returned were not those most strongly reminiscent of Gill, Jones or the Ditchling community, but the more abstract yet rooted representation of ‘Observatory and Stable’, for example, with the circles of the cylindrical telescope, the curve of the shooting star, the triangles and rectangles of the observatory-cum-stable. In ‘Rollesby Church’ on the Broads, the sweep of sun and moon and wave of water of the Broad and grass of the churchyard contrast with the blocks of stone of the church, firm against the pull of tides.

This volume is a foretaste of the book of broadsheets in preparation by the Whittington Press. Here John Grice has produced an immaculate volume. The engravings are crisp, showing again why Zerkall mould made is so often the paper of choice for this kind of production. The informative captions to the engravings are in a discrete and subtle green echoing the binding and endpapers; each engraving benefits from a generous amount of space on the page. All shows the level of judgment and precision in execution that is associated with John Grice.

Alan Powers’s useful and anecdotal foreword, which suggests an interesting link between Anderson’s work and that of Ian Hamilton Finlay, ends with a plea for more. Until more comes, you will have to make time to seek out his work in, for example, the farms and churches of East Anglia: enclosures in a sense, yes, but seen through airy, sunlit and joyful eyes.

180 copies. 35 specially bound with a signed print by the artist, £130; standard edition, £80.

Evergreen Press

Unit 23m Bond’s Mill,

Stonehouse, Gloucester GL 10 3RF

01453 791907

www.evergreenpress.co.uk