Alan Powers and James Russell, Eric Ravilious: The Story of High Street, Mainstone Press, 2008. £160

‘Here at last, after all this long time, is “High Street” and I send you a copy as a sort of Christmas present . . .’ wrote the English artist Eric Ravilious (1903–1942) to his former lover Helen Binyon, on 28 October 1938. Seventy years later, almost to the day, the Mainstone Press published what is effectively a facsimile of Ravilious’s now much-coveted last book, along with two twenty-first century commentaries. Historical context for the 1938 book is provided by the art historian Alan Powers’s informative account of its genesis; and by the social historian James Russell’s account of his and the publisher’s research into the locations of the real shops that the artist illustrated in High Street, and how the shops have changed since then.

Eric Ravilious: The Story of High Street was high on the artist’s admirers’ Christmas wish lists last year, despite several other new books about him having been published during 2008 by private presses and trade publishers. But there is little danger of generating a glut in the insatiable Ravilious market. The artist and his inter-war contemporaries, including Edward Ardizzone, Edward Bawden, Barnett Freedman and John Nash, depicted the landscape and life of rural and urban England during a period of accelerating change. Although they are all admired, Ravilious is particularly revered, perhaps because he died at the age of 39, while serving as an official war artist stationed in Iceland. His continuing appeal puzzles some North America readers, but he has advocates there too. ‘O’Connor’s my favourite wood engraver of them all,’ wrote the American artist Vance Gerry to John Randle of Matrix twenty years ago. ‘Ravilious next.’

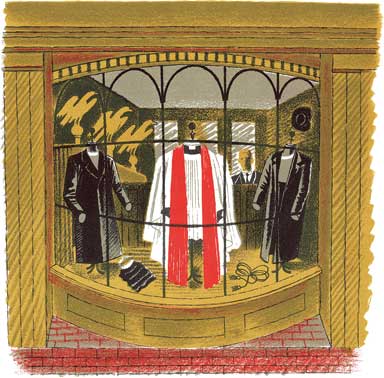

In 1924 Ravilious and his friend Bawden jointly designed ‘The Christmas Bookshop’, an advertising insert for the December 1924 edition of The Studio. It was one of their earliest published designs, drawn while they were still students at the Royal College of Art. It shows a bow-fronted window, with a frock-coated bookseller standing proprietorially in the shop’s doorway. Helen Binyon and Ravilious had considered collaborating on an alphabet of 26 shops in 1935, when the artist began scouting for likely subjects. ‘On the way to Euston I came across a perfect addition to the series – a milk shop, a beauty altogether and if you ever come with me I must show it to you,’ he wrote to Binyon on 27 November 1935.

His father having been a shopkeeper might have contributed to Ravilious’s interest in shops but, as Powers explains, the artist and his contemporaries were enthusiastic about Soviet books for children, illustrated with lithographed scenes of everyday life. Illustrated French children’s books depicting shop fronts, such as those published by Père Castor, were also popular. By 1936, High Street had become a series of illustrations, in search of a publisher and a text. Ravilious offered it to the Golden Cockerel Press, who declined it. But Noel Carrington, adviser to Country Life Publications, liked the idea and commissioned Hamish Miles to write the text. Unfortunately Miles died before writing it, so J M Richards was commissioned in his place. He researched the subject assiduously, questioning various shopkeepers and even obtaining a written quote for diving equipment from Siebe, Gorman & Co. Ltd, suppliers of ‘Everything for the Diver and for Submarine Operations’.

Although it was not included in High Street, Ravilious’s pencil and wash sketch of the milk shop is reproduced opposite the title page of the Mainstone Press book, which is illustrated throughout with the artist’s surviving preparatory drawings. He made detailed annotated sketches on the spot, from which he later drew edited versions with simple, incisive pencil lines, and eventually transferred them to lithographic plates. He quickly mastered the technical skills to achieve a wider range of colours in his lithographs than the four ink colours used, by overprinting transparent inks. This is evident from his subsequent reworking of three High Street shops, published in Signature 5 in 1937.

High Street had a print run of 2000. It was reviewed well on publication, with copies selling at seven shillings and sixpence each. Its importance in Ravilious’s oeuvre was assured, and a copy was displayed in the memorial exhibition organised by the Arts Council in 1948. But the confl ict that killed the artist also destroyed his High Street lithographic plates, when the Curwen Press was bombed. This ruled out any post-war reprint of the book.

Ravilious’s lithographs are magnificent, but the book itself was poorly designed, its pinched margins cramping both text and lithographs. Its design is less elegant than other inter-war trade books, including Adrian Bell’s Men and the Fields, illustrated with six full-page lithographs by John Nash, which Pat Gilmour described in 1977 as ‘one of those nine shillings and sixpence bargains that still make one gasp’. It is unfortunate that individual lithographs from High Street are seen to better advantage when generously mounted, fetching ever higher prices which encourage dealers to break up damaged copies.

The Mainstone Press chose a page size of 26.5 × 19.5cm for The story of High Street, after the publisher had observed that the ‘Knife Grinder’ lithograph looked better when printed on the more generously-sized pages of Country Fair (The Country Life Annual, 1938). Bound in dark blue cloth with a front label reproducing Ravilious’s watercolour sketch of the ‘Submarine Shop’, the book has a slipcase covered in the same fabric.

Many of the shops illustrated in High Street were already anachronistic, with their narrow specialisations, when chain and department stores were beginning to impose uniformity in retailing, and also with their old-fashioned stock, such as paraffin lamps and ceramic hot water bottles. Only two of the 24 High Street shops are still to be found at their original addresses: clerical outfitter J Wippell and cheesemonger Paxton and Whitfield. But Ravilious’s lithographs in the original book, and the excellent reproductions in the new facsimile, provide nostalgic insights into 1930s retailing, now that the majority of people serve themselves in supermarkets or virtually, via internet shopping.

Mainstone Press. Sparham, Norwich NR9 5PR. Tel: 01362 688395.

Email: info(at)themainstonepress.com

http://www.themainstonepress.com

Colin Martin is a writer and collector, who possibly spends more money on illustrated contemporary private press books than is prudent.