Lubki (singular lubok) are the woodblock prints which served as folk literature and graphic art in Russia until 1917. Lubki could be purchased for a kopeck or two, black and white or colored, in the streets, marketplaces, church doors and in front of monastery gates of old Russia. They were used to decorate the homes of the poor, often substituting for more expensive painted wooden icons. The great masters of the Russian Avant-Garde, the Constructivist, Suprematist and creators of Abstract painting – Kandinsky, Malevich, El Lissitsky, Rodchenko Stepanova, Larionov, Gontcharova, and Chagall – all claimed to be influenced by the simple, primitive directness, the specifically Russian iconography and the charming playfulness of these prints.

The Russian word lubki derives from lub, the carvable inner bark of the linden tree on which woodblocks were originally engraved. The word lubki also stands for ‘bast’, the fiber that grows between the inner wood and the outer bark of a linden tree. Bast was also used to make the baskets in which lubki were stored before they were sold. The Latin word for book, liber, is also derived from the Sanskrit word lupti or lubh, meaning ‘to peel, or strip away’ – referring to the bast or inner bark of a tree. In the ancient world, tree bark was used as writing material where papyrus or parchment were not available. The word lubki was also connected with Lubianka Street, the street of the printers in old Moscow. Lubianka Street, and its infamous prison, were named after lubki.

Printing was done quickly. Engraved blocks of linden wood were carved and inked with a mixture of soot and burnt sienna dispersed in boiled linseed oil, simple presses speeded up the production and whole villages colored the prints with natural dies – reds, purples, yellows and greens. Exposed to light, the prints faded rapidly – but no matter: new lubki were cheaply available.

The pictorial messages conveyed by lubochnye kartinki (printed pictures) are straightforward and easily understood by readers and non-readers. Drawing and lettering were integrated with the background or negative space. Lettering was used to frame an episode or to isolate a series of vignettes surrounding the central figure or motifs. As on icons, perspective and scale were simply ignored.

Travelling peddlers, offeni (singular ofenia) hawked lubki from village to village. Favorite topics were advertisements, political or religious events, often depicted in satirical form. Biblical scenes were popular as well as folk tales – Russian bilini recounting exploits of legendary folk heroes – the bogatyri, such as Sadko or The Lay of Prince Igor. Calendars, farmer’s almanacs, astrological guides, hagiographic collections, manuals depicting the latest fashions and guides on how to choose the right wife – with instructions on how to achieve wedded bliss by beating her into submission – sold briskly. Azbuka (alphabet books) printed on rough gray paper were common.

Printed and illustrated books had been introduced into Russia – into the cities of Kiev, Lvov and Moscow – by German Hanseatic merchants. The Biblia Pauperum, the Ars Morendi, the Piscator Bible, the 1514 Wittenberg Bible, or the Nuremberg Chronicle, and engraved prints by Lucas Cranach, Albert Dürer and other Western European artists, supplied inspiration for the earliest lubki. Tsar Ivan the Terrible (1533–84) established the first printing press in Moscow and commissioned the first Russian printed book – an Apostol (Acts and Epistles of the Apostles). Two Russian printers, Ivan Fedorov and Peter Timofevich began printing the Apostol on April 18, 1563, and finished it in March, 1564. As frontispiece they included a woodcut portrait of the Evangelist Luke sitting in his scriptorium, writing his Gospel.

The earliest surviving lubki were printed near Kiev in 1625. They were commissioned by the Russian Orthodox clergy of the Monastery of the Caves near Kiev. Lubki depicting Russian saints, their miracles and teachings were useful in their never-ending feuds with their Polish, Roman Catholic neighbors.

During the reign of the first of the Romanovs, Tsar Michael I (1613–45), a Russian chapbook (now at the Bodleian Library, Oxford) was engraved by Pamva Berynda. Dated 1628–9, it includes twelve hand-painted woodcuts, one for each month of the year. Between 1645 and 1649, Ilia the Monk cut 132 of the 150 blocks needed to illustrate a broadside Bible similar to the German Biblia Pauperum of 1475. Between 1646 and 1661 Master Prokopii engraved 24 plates depicting the Apocalypse. These pictures, the icons and church frescoes, were copied again and again, becoming ever more primitive and ever more direct in their approach.

Around 1690, a large (85 by 90 cm) secular calendar was printed in Moscow’s Lubianka Street. The Sun, the Signs of the Zodiac and the Four Seasons, one of the most popular of all lubki, was printed from nine wood blocks. It reproduces the painted ceiling of a dining room in Tsar Ivan the Terrible’s new wooden palace at Kolomenskoe. In the center is the Sun, a strong folk-motif in pre-Christian Russia. The Four Seasons are personified within large roundels as classical Goddesses. Popular lubki passed through many editions. Copyright laws did not exist. Alterations in the iconography and the addition of new materials became common.

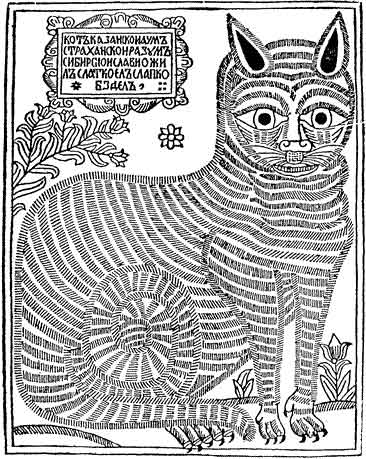

Lubki makers could become famous. Vasili Koren (1640–after 1696) was one of the most prolific of early lubok masters. In 1696, during the reign of Peter the Great (1682–1725), he engraved the frontispiece and 35 full pages of biblical and apocalyptic subjects after designs by the poet/painter Gregori. Koren had a host of pupils and followers. Since lubki were unsigned it is difficult to determine the identity of their engravers, but we know that it was Vasili Koren who created the most famous of all lubki – ‘The Great Cat of Kazan,’ a print measuring 27 by 35 cm. On the upper left, we read, in Old Slavonic orthography, a satirical allusion to Tsar Peter the Great:

The Cat from Kazan,

In the manner of Astrakhan,

By reason of Siberia,

Lives gloriously,

Manages agreeably,

And farts sweetly.

Tsar Peter commissioned Vasili Koren to design what has become the best known lubok in the United States, due to its frequent inclusion in history texts – ‘Peter the Great Cuts off the Beard of an Old Believer Boyar.’ After visiting Versailles and being charmed by the elegance of Louis XIV’s courtiers, Tsar Peter issued a ukase (edict) forcing Russian boyars to shave off their beards or pay a hefty fine of 130 rubles. The lubki’s inscription proclaims that ‘the barber himself will cut off the beards of the trouble-makers.’ The ultra-conservative Old Believer boyars resisted being shorn, claiming that without their beards, the chief ornament of the male sex, men are not allowed to enter Paradise. Tsar Peter was declared a heretic – the very Anti-Christ. In January 1725, when Peter the Great died, the Old Believers had their vengeance. Vasili Koren was commissioned to design ‘How the Mice Buried the Cat,’ a 33 by 56cm lubok printed from two side-by-side wood blocks. The dead Cat is, of course, Tsar Peter himself as the peculiar smelling Cat of Kazan, who, as the inscription declares, may be dead but ‘still possesses the spirit of Astrakhan and the wisdom of Siberia.’ Eight lively mice from the city of Riazan pull Tsar Peter’s sled through the January snow. Standing at the back of it a mouse holds a shovel aloft. On the left, a mouse beats a drum announcing the funeral cortege, while other mice carry refreshments for the wake: loaves of bread, a barrel of brandy and a tub of beer. Some mice represent territories which Peter won in his battles with Sweden. Justice is served: above the dead Tsar, a group of happy mice ride in a European cabriolet and play the sort of horns and bagpipes which Peter introduced to Russia.

In 1839, following a period of political insurrection, Tsar Nicholas 1 (1825–55) established strict censorship of the topics depicted on lubki. Those prints which offended the Tsar, his family or the Russian Orthodox church were ordered to be destroyed. Luckily a few lubki aficionados managed to save a few examples.

Among the best known collectors was D. A. Rovinskii, whose Russkie Narodnye Kartinki (Russian Folk Pictures) was published in 1881 in an edition of 250 copies by the St. Petersburg Academy of Science and State Paper. Surviving copies are extremely rare. Rovinskii’s book consists of two large volumes of text and three volumes, in seven parts, containing 450 of the choicest lubki printed from 1629 to 1839. Rovinskii’s book included lubki in two states – hand colored and black and white, but currently the copies at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and the Library of Congress, lack the black and white plates. In 2002, D. A. Rovinskii’s Russkie Narodnye Kartinki was reprinted, with smaller plates and in one volume, by Tropa Troianova of St. Petersburg.

Nicholas Teleshov, in his Recollections of a Writer, described the selling of lubki in a Russian country fair around 1900 and listing the most popular titles offered to the moujiks (peasants):

While ofeni wander through the crowd with lubok on various subjects – Fallen Adam, Life After Death in Paradise, Life in Hell, Among Green and Red Devils with Long Pitchforks, Horns on their Heads and Tufts at the End of their Tails, in a stall for moderate-priced goods sits a man with an ascetic-looking face selling Bibles, saints’ lives, and other books, very inexpensive and well-printed by a society promoting soul-saving reading. But despite the strict days of Lent, this commodity is not in demand. ‘Who wants the Seven Sins? Who wants The Future in Another World?’ gaily shouts a strolling ofenia, holding at head’s level his pictures of green and red devils, which are in demand by the vegetable growers who come to this market . . . and especially by their wives.

Professor Adela Roatcap is an art historian in San Francisco with a special interest in printing and pochoir.