Maron Andrews. London. Primrose Hill Press. 2003. £45.

In 1975 I saw the imaginatively illustrated catalogue to an exhibition of Robert Gibbings’ work at Reading University, and it gave me the first inkling of the fascinating and colourful personality of an engraver whose work I had always enjoyed. The exhibition was organized by Martin Andrews and Sue Walker, then students at Reading, and this book is therefore the culmination of a thirty-year interest in its subject by Martin Andrews.

Gibbings would have been delighted by the result. Martin travelled to Cork to research the Gibbings family (and an interesting and often distinguished lot they were), and Los Angeles to examine the incomparable Vodrey collection of Gibbings material at the Clark Library. He has throughout also en- joyed the confidence and encouragement of Patience Empson, who sailed with Gibbings to the South Seas in 1946, worked as his amanuensis up to the time of his death. and just lived to see the publication of this book.

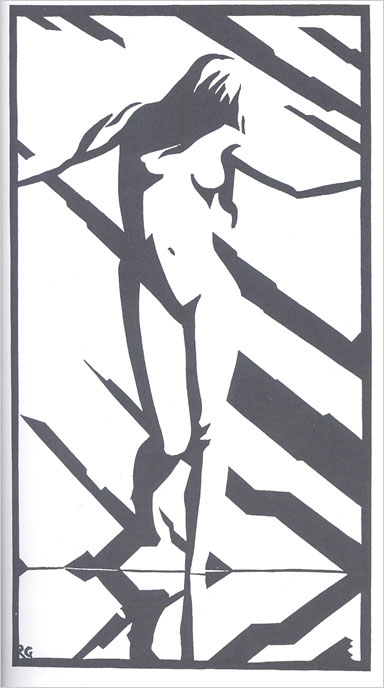

‘Clear Waters’ wood engraving by Robert Gibbings.

Martin is therefore in a unique position to write about Gibbings’ unusual personality — his early diffidence, the horrors he encountered at Gallipoli, and his determination to be an artist in spite of family pressures in other directions. He married Moira in 1919 when he was thirty (his father-in-law Colonel Pennefather looks none too happy in the wedding photograph) and her encouragement and organizational talents played a significant role in the success of the Golden Cockerel Press which Gibbings bought from Hal and Gay Taylor in 1923, not long after he had been commissioned by them to illustrate The Lives of Gallant Ladies.

Gay had written to Gibbings to say the press was closing due to the ill health of her husband Hal. That evening Gibbings dined with his friend Huben Pike, a director of Bentley Motors.

‘How’s things?’ he asked. ‘Rotten’, I said. ‘Just lost the only decent job I’ve had for months’, and I explained what had happened. ‘Why don’t you buy the Press?’ said Huben. ‘Its just what you want: ‘Haven’t got the money’, I answered. ‘I’ll lend it to you’, he said. ‘Go down on Monday and, if you like it, buy it.’

Gibbings went down, stopped the two compositors from binning the Caslon, and bought it.

At the Golden Cockerel Press Gibbings came into his element. He had earlier written to Tom Balston, then a partner at Duckworths. ‘I should very much like to do some decorations for really first class books, especially when it would be possible to keep in touch with the printer and treat the book as a whole, not so many pages with so many illustrations.’ Balston bought the last print from the edition of ‘Clear Waters’, the prime example of Gibbings’ ‘vanishing line’ technique, which played its part in placing wood-engraving amongst the vanguard of modern art in the 1920s, before it gained its reputation among the hedgerows from which it is still struggling to escape.

Projects at the newly run Golden Cockerel could begin in a delightfully un-Doves-like way.

One morning before breakfast we found no type free but the small 11 pt. My wife put her hand out to the nearest bookshelf, drew out the first book, Thoreau’s Walden, and opening it at random came to the essay ‘Where I lived and what I lived for’. Crown paper folded many times gave a small enough page; the type was set and printed, leaving space for the engravings to be added later. So came into being this minute volume, & another unemployment problem was solved.

But thanks to the skills of the three craftsmen Gibbings had inherited, the productivity of the press was remarkable. Five books were published in the first year, eleven in 1925, thirteen in 1926, and seven in 1927. One of the Press’s most important relationships was with Eric Gill. Gill had initially refused Gibbings’ offer of work ‘because I was not a Catholic’. But after Gill’s break-up with Hilary Pepler at the St Dominic’s Press he agreed to let Gibbings print a volume of his sister’s poems, with his engravings, Sonnets and Verses. This led to an instant rapport between the Gibbings and Gill (who drew a remarkably sensitive figure study of Moira). As Fiona MacCarthy remarked in Matrix, ‘Gill and Gibbings were prize boosters of one another’s ego: The culmination of this relationship was The Four Gospels in 1931, still regarded as one of the noblest books of the century.

Gibbings sold the press to Christopher Sandford in 1933, ostensibly due to the slump, but perhaps he also longed for the freedom to sculpt, paint, engrave and travel, and his family life had become more than a little complex. In 1936 he joined the staff of Reading University to teach book design and production, a move that was later described as ‘a most enlightened and adventurous appointment for an academic body to make.’ Gibbings’ large frame and personality went down well with staff and students alike. In 1939 he built a flat-bottomed boat, the Willow, and rowed down the Thames. The result was Sweet Thames Run Softly, the first of a whole series of travel books illustrated with his wood-engravings which had a great success in wartime Britain, and later on in America, and only ended with Till I End My Song in 1957, the year before his death. Their success enabled him to give up teaching, and in 1946 he made a two-year trip to the Pacific. Over the Reefs (1948) was the result of this book, just as Blue Angels and Whales (1938) had been the outcome of an earlier trip to Bermuda and the Red Sea, when he had famously put on diving gear and illustrated the coral underwater scene from life with a graphite pencil on a sheet of xylonite. He and Patience returned to live in Long Wittenham in Berkshire, where he died in 1958.

Martin Andrews leads us skilfully through the maze of Gibbings’ eventful life, which he records with a lightness of touch that never renders it indigestible. The book is a model of design and production, and the matte art paper on which it is printed is an acceptable price to pay for the excellence of the many reproductions it contains.

John Randle and his wife Rosalind Randle are the proprietors of Whittington Press in Gloucestershire. John is also president of the Fine Press Book Association.