Part 1: The White Elephant and The Fabulist, 1913–1921

Note: Part two of this three-part series will appear in the Spring 2012 Parenthesis.

Front cover, White Elephant, 1915.

HINGHAM—Most readers of Parenthesis are familiar with the work of William Addison Dwiggins (1880–1956) in the areas of typeface and book design. Dwiggins planned the formats for hundreds of trade books for Alfred A. Knopf, created fancier books for The Limited Editions Club, Random House, The Lakeside Press, and Crosby Gaige, and designed types for the Linotype Corporation. Of these, Caledonia and Electra are the best known. However, his many other artistic activities are not so prominent: he was an accomplished artist in puppetry, from marionette engineering and construction to the design of costumes, sets, and lighting; an expert kite-maker; a writer of fiction, fantasy, essays on art and printing, and even anti-war pieces. Throughout his career Dwiggins issued occasional printed pieces via his own private press, a marvelous body of work that I will highlight later in this series. This first article covers his early years in Boston; the subsequent articles will highlight his productions from 1922 through the early 1950s.

Armed with a sharp wit and an insightful appreciation of human nature, Dwiggins (‘WAD’) often used humor to drive home points that he wished to make about serious topics. He produced articles and essays under his own name or that of his imaginary colleague, Dr. Hermann Püterschein. He wrote plays for his marionettes, then watched as they were performed in a purpose-built theater of his own design. Dwiggins also wrote a series of fantasy tales—‘The Athalinthia Stories, translated from the Metrelingua Permé and extended with Images and Diagrams’—that captured the sights and scents of exotic places while regarding human aspirations and foibles with particular tenderness and Puckish humor. His personal work was peppered with references to literary classics, revealing his own passions for this subject. All of these activities found expression in his private press work.

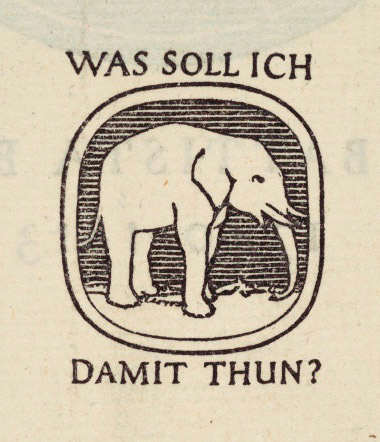

First White Elephant pressmark, 1913.

Following a childhood in Ohio and Indiana filled with drawing and woodcarving, Dwiggins attended the Frank Holme School of Illustration in Chicago from 1899–1903, where his teachers included Frederic Goudy, John McCutcheon (Pulitzer prize-winning cartoonist), the Leyendecker brothers (cover artists for the Saturday Evening Post, Vogue, Vanity Fair, and other national magazines), W.W. Denslow (illustrator of The Wizard of Oz) and Frank Holme himself (the greatest living newspaper sketch artist at a time when important news was communicated through illustration and text rather than radio or television).

After an unsuccessful year running a design studio in his home town of Cambridge, Ohio, Dwiggins married his high school sweetheart Mabel Hoyle, and then accepted Fred and Bertha Goudy’s invitation to join them in Hingham, Massachusetts, a small town just outside Boston. Although the Goudys soon discovered that the Village Press could not survive in Hingham, and moved to New York, the Dwigginses liked the town and elected to stay. Dwiggins worked from home through the first six years, joined the newly founded Society of Printers, and was befriended by Boston’s eminent printer Daniel Berkeley Updike, whose Merrymount Press gave him a steady stream of commissions for book title pages, calligraphy, and illustrations. In 1910 Dwiggins moved his studio to downtown Boston and quickly became a mainstay of the advertising community, although his heart remained firmly in books and letterforms.

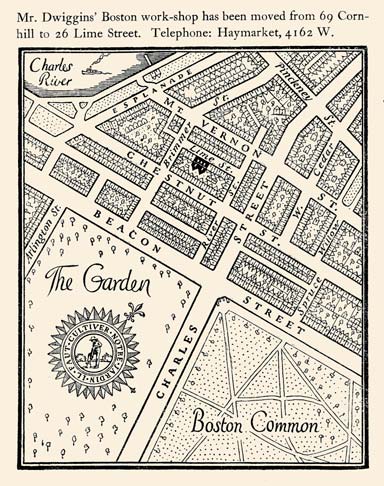

In 1911 the Dwigginses bought a house that could accommodate printing equipment, so into the spare bedroom came an old engraver’s hand-proofing press and 150 pounds of Caslon 471 type. At a time when much of his work centered on high-pressure, deadline-driven commercial projects, the private work was a welcome diversion. Dwiggins called his press The White Elephant, and furnished it with a motto: Was Soll Ich Damit Tun? (What Shall I Do With It?). The first public output of the press was a 1913 keepsake in honor of Giambattista Bodoni, to accompany a talk at the Society of Printers. Official issue Number One appeared in January 1915 as a moving notice, with hand-lettered front cover, a map of the new studio’s location, and a print of a freight train. (This train may well have been one from central Massachusetts, where WAD made frequent visits to the Dyke Mill printing office of his friend Carl Purington Rollins. Bruce Rogers was also at Dyke Mill during this period, while he worked alongside Rollins to produce The Centaur.)

Dwiggins’ younger cousin Laurence B. Siegfried (1892–1978) shared studio space with Dwiggins in downtown Boston. Siegfried became editor of the American Printer from 1929–1940 and later taught at Syracuse University’s School of Journalism. At some time in the early teens, the two cousins were at a family gathering, helping with meal preparations. While trying without success to polish a pewter pitcher, Dwiggins remarked in frustration, ‘I can’t make the damn pewter shine!’ Siegfried seized upon this and the two began to imagine an entire family of German immigrants descended from Thedam Püterschein, with male and female members who corresponded to Dwiggins, Siegfried, and others in their circle. Notorious among these was WAD’s character, the brilliant but pompous Dr. Hermann Püterschein, who would create many drawings and articles in the decades to come. Dwiggins felt that using ‘HP’ as a nom de plume would accomplish more than if he were to sign everything under his own name.

To divert themselves from their regular work and ‘express their peculiar but potent individualities,’ Dwiggins and Siegfried published three issues of The Fabulist between 1915 and 1921. They printed the first two numbers on the press in Dwiggins’ spare bedroom; Rollins printed the third on his press at Yale. The cousins indulged in other projects during these years—some of them quite silly—but the Fabulists remain the most compelling.

Number One (eight pages, edition size unknown) featured an exhaustive description of the Püterschein family, color line drawings of Aphrodite and Paris, and a bleak Dwiggins short story, which was later selected for Houghton Mifflin’s Best Short Stories of 1915. The issue closed with the Italian proverb, Se non è vero è molto ben trovato (If it’s not true, it is very well conceived), and a pressmark that featured the original pewter pitcher, since the Püterschein brothers were the ostensible publishers of The Fabulist.

Decorated initial from a mailer promoting The Fabulist Number Two.

The Fabulist Number Two appeared in early 1916 (eight pages, edition of 300). By this time Dwiggins had begun experimenting with the stamped patterns and stencils that were to become one of his trademarks. The partners had solicited a contribution from British playwright and fantasy writer Lord Dunsany (1878–1957), so his story, ‘East and West,’ constituted the bulk of the issue. Dwiggins created two stencil illustrations in multiple colors to enrich Dunsany’s narrative about a peasant observing strange events in North China. On this occasion the publishers closed out the issue with a quote from Daudet’s Tartarin of Tarascon: ‘Fen dé Brut! Faisons du Bruit!’ (Let’s make some noise!).

Map showing location of Dwiggins’ new ‘work-shop,’ White Elephant, 1915. Note the Candide motto in the compass rose.

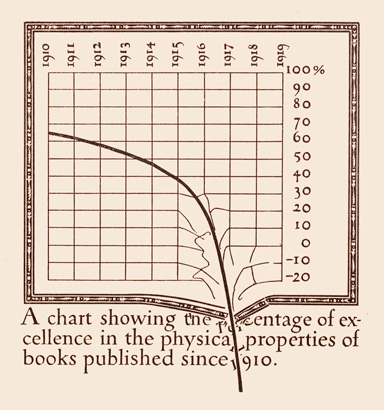

During the period from 1910, when he moved his studio into Boston, until the end of the 1920s, Dwiggins earned the bulk of his income from advertising work, but his deepest desire was always to design books. At the close of World War I he had served as acting production manager of the Harvard University Press and had formed a very low opinion of the practices followed by publishers and book manufacturers. In 1919, Dwiggins and Siegfried created a fake series of interviews with publishing magnates and book salesmen, delighting in exposing the shoddy quality of most trade books and the cavalier attitudes of the people who made them. Extracts from An Investigation into the Physical Properties of Books as They Are at Present Published covered twenty pages (plus four blanks) and sold for fifty cents. (Edition size not stated, but it was likely at least 300 copies.) This time the publisher was The Society of Calligraphers, another fiction created by Dwiggins to aid him in his commentaries about graphic arts and printing. (We will see much more about the Society in part two of this series.) Although the writing in this ‘investigation’ was clearly satirical, Dwiggins later recalled that one publisher actually contacted him, concerned that one of his employees had consented to an interview! This modest booklet caused a major stir in the book world of the time, and certainly contributed to Dwiggins’ visibility as a discerning designer of books; nevertheless, it was not until 1926 that he began to receive regular commissions for book design.

Chart from ‘. . . Physical Properties of Books . . .’ , 1919.

Meanwhile, Dwiggins applied his powers of imagination and his craft skills to other areas of creative expression beyond his regular commercial work. For the Hingham house he designed furniture, carpets, lampshades, fireplace screens, and a weathervane that reported wind direction at a remote location inside the house. He painted large murals on the walls of the dining and living rooms, depicting Sinbad’s home port, and Mana Yood Sushäï, the creator god from Lord Dunsany’s 1905 story The Gods of Pegäna.

By the time of The Fabulist Number Three (twelve pages, edition of 500) in late 1921, Dwiggins’ hand-lettering skills had grown even stronger; although Carl P. Rollins undertook the presswork at the Yale University Press in New Haven, the text for the entire issue was composed of Dwiggins’ own roman lettering, accompanied by decorations built up from tiny elements to make larger patterns. The beauty and readability of the text also gives clear indication that he would soon become an important designer of printing types. Number Three opened with an introductory statement from Dwiggins, which expressed beautifully and vividly what he felt was important in life, and then presented a poem (ten pages of lettering) by contemporary poet John French Wilson.

The opening statement from The Fabulist Number Three, written by Dwiggins at age forty-one, reveals much about his beliefs and values.

Dwiggins’ personal projects gave him the chance to be whimsical, romantic, critical, literary, and experimental in ways that his commercial work simply could not allow. Through these obscure treasures we glimpse a cultured man who was as skilled with words as he was with images . . . a man fully in love with life.