I am partial to small books. (Not miniatures, which I dislike; they are bibliostunts, the freak show of the book arts. Happily, they are so tiny that they easily get lost.) By small books I mean ones that measure about 4 by 6 inches or a bit more — duodecimos. They are easy to handle, easy to shelve and difficult to design. They also tend to be overlooked and hence underpriced.

Why this neglect? Big books, certainly, can make more of a show, particularly with illustrations. They are easier to show off to one’s friends and justify to one’s spouse. Big books insist on being noticed; they do not crouch down on the shelf, as small books do, modestly (or is it proudly?) defying their owners’ efforts to find them. Big books tend, too, to have big texts: classics of literature, wonders of nature, diaries of rural clergymen. Not for them topics that enchant with their irresistible inconsequence, such as (to take two real examples) A Little Book of Cheeses and Hop Scotch.

So here is a tribute to some of the small books that I admire. I have chosen ones whose texts are as beguiling as their design. And I have tried to steer clear of examples that need no rescue from obscurity. Many of Bruce Rogers’ finest products are small — in fact, thirteen on his list of 30 favourites — but they are also well known. I’ve resisted the temptation as well to list pretty much the entire output of the Hammer Creek Press, all of which were small because they were printed on a minuscule hand press in John Fass’s bedroom at a New York YMCA. I find it impossible to select a favourite among Fass’s beautifully set jewels, which sparkle with their designer’s shy originality.

A Butler’s Recipebook

Edited by Philip James 45 pages, Cambridge University Press, 1935

This is the first book to carry wood engravings by the incomparable Reynolds Stone. No gardener with his shears has ever been able to shape vegetation in the elegant way that Stone manages with his graver. Here he offers a series of amiable country vignettes that perform the useful service of gentling the often brutal text that accompanies them. For these are recipes from a more roughhewn age (the date is 1719) when the distance from slaughterhouse to kitchen was not so great and when a remedy’s effectiveness was thought to increase with the ghastliness of its ingredients. Some cases in point:

To Kill and Roast a Pig Take your Pigg and hold the head down a Payle of cold Waner untill Strangeled…

A Snail Waner good in a Consumption or jaundis to clear the Skin or Revive ye Spirrits…

This dubious specific was made by mixing crushed snails (shells included) with squashed earthworms, adding a mess of herbs, then marinating the lot in ‘the strongest Ale you can gett’ plus ‘two gallons of the best sack.’ The recipe does not make clear that the patient was supposed to drink this potion, but I fear he was.

A Remedy for the Plague Take a Cock Pullet and pluck of the fethers of the taile or hinderpart till the rump be bare, then hold the bare [rump?] of the said Pullet to the sore and the pullet will gape and labour for life and in the end he will dye. One was to repeat the process with more pullets until they stopped dying, at which point one would be cured.

The Cambridge University Press must have enjoyed some success with this book, because two years later it produced another in the same vein called Early English Recipes. This one, drawing on 15th century cookery, is distinctly less brutal. Its wood engravings, by Margaret Webb, are in a lighter vein than Stone’s, though they do include a scene of a woman stitching together the famous Cokyntryce, which joined the front end of a pig to the rear end of a capon, and vice versa. The recipe is sketchy on precisely how to cook this monster, and it may not have mattered much. Clearly the main thing was the presentation.

Mademoiselle from Armentières

Illustrated by Alban B. Butler, Jr. 2 vols., 71 and III pages, Press of the Woolly Whale, New York, 1930 and 1935

For many years Melbert B. Cary, Jr. produced books to commemorate Armistice Day at his Press of the Woolly Whale. Some were earnest in tone. This was a merciful exception.

World War I is now so distant that some modern readers may need a few words of explanation about the once-famous Mademoiselle. She was an archetypal camp follower celebrated, fondly but often scatologically, in hundred of lyrics of a soldier’s song whose basic format was as follows: Oh,

Mademoiselle from Armentières,

Parlez-vous,

Oh, Mademoiselle from Armentières,

Parlez-vous,

She had four chins, her knees would knock,

And her face would stop a coo-coo clock,

Hinky dinky parlez-vous.

Cary gathered together every lyric he could find, dropping in only an occasional ellipsis or euphemism when the language got too raw for the ears of the Woolly Whale (although the rhyme scheme left little doubt which word was intended). The second volume was made necessary by the enormous response to the first. Cary invited ex-servicemen to write him with lyrics he had missed, and they replied with a fusillade of Armentièresiana. Certain topics stand out in the midst of this scabrous variety, suggesting that the soldiers’ moments of relief behind the lines, however greatly treasured, were not much healthier than life in the trenches. ‘Cooties,’ pox and poor bathing habits are regular themes and a favourite rhyme for Armentières is ‘underwear.’

The second volume also contains some interesting research into the origins of the song. It turns out to have antedated World War I by several decades at least, having started out as an English drinking song whose refrain went: ‘Skiboo, Skiboo, Skiboodley boo, Skidam, dam, dam.’ (It must have sounded catchier than it reads.) Alban Butler’s illustrations suit the text perfectly. They are saucy but never stray into the deeper bogs of raunch. In fact, the books have a sort of innocent charm that was entirely lost on the U.S. Post Office, which gave Cary trouble for sending obscene material through the mails.

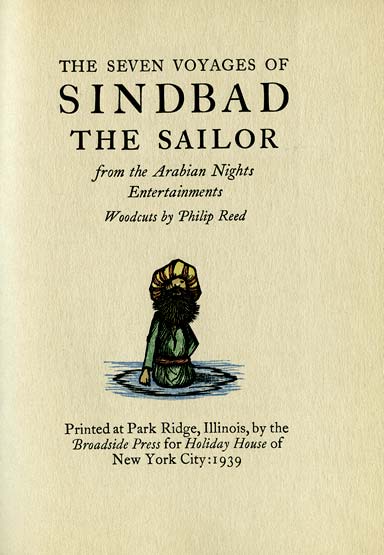

The Seven Voyages of Sindbad the Sailor

Woodcuts by Philip Reed 71 pages, The Broadside Press for Holiday House, New York, 1939

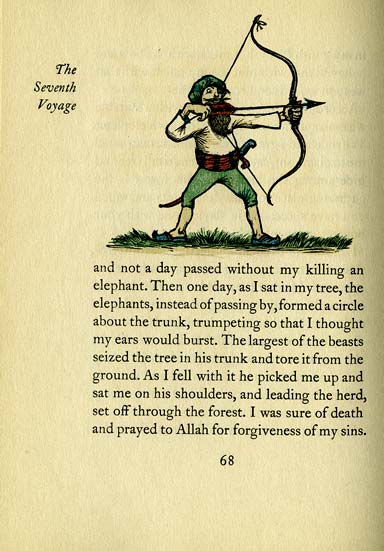

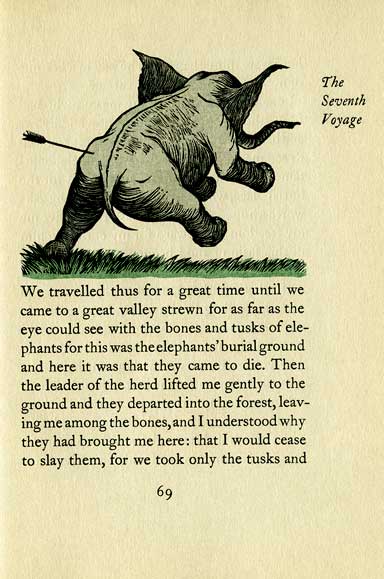

Here’s one that’s even more obscure, though 1300 copies were printed. It’s a lovely book, reminiscent of the beautiful little books (William Tell, The Red Shoes) that Willi Harworth or Fritz Kredel illustrated in Germany. The woodcuts are deft and amusing — Philip Reed had a way with turbans and facial hair. They are coloured (printed, not hand-coloured) with delicacy and taste. The paper is nicely chosen: a pale grey (the colophon identifies it as Whitehead & Alliger’s TJ paper); and the book is neatly designed, set in Caslon Old Face, with italic running heads for the chapters at the shoulders. It’s one of those miraculous cases where everything — type design, paper and illustrations — comes together with something approaching perfection. The book deserves to be much better known.

When I bought my own copy, three years ago, I hadn’t the faintest idea about its origins. I hadn’t run across anything by Philip Reed and the Broadside Press, and it was only the stimulus of preparing this article that prompted me to do a little research. The usual reference books on private presses were of no help. But Sindbad’s colophon did disclose that the book had been printed in Park Ridge, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. A call to the Newberry Library seemed to be in order, and presto! Paul F. Gehl steered me to enlightenment. Philip Reed, a printer as well as an illustrator, founded the Broadside Press in 1930. At first he did mostly Christmas books and other specialty printing. But his timing was unfortunate: the Depression cast a pall over the business, and his work never achieved the circulation that it deserved. Sindbad was a rare commission (his brother John did the typesetting). Philip Reed’s other two notable sets of illustrations appeared in an edition of Thurber’s Many Moons (1958) and a Mother Goose (1963), but they were done for other publishers. His private press (successively renamed the Monastery Hill Press and the Printing Office of Philip Reed) was no more.

Images reproduced courtesy of Lee Auchincloss Niven.

Kenneth Auchincloss was Editor-at-Large for Newsweek magazine.