The Pear Tree Press of Orewa, a town north of Auckland on New Zealand’s North Island, came into existence in a shed sheltered by a large pear tree, hence the name. At the time of my initiation into print in the late 1980s I had yet to hear of James Guthrie’s press of the same name. Initially, I was given the opportunity to acquire an Albion press. I was seduced by this 1832 cast iron monster, a machine so simple and well constructed that it would outlive any contemporary press. The quest for letterpress knowledge and equipment had started. With my background in graphic design, a field which was moving into an era of rapidly changing technology, involvement in a hands-on craft had considerable appeal.The Press has now grown to include the Albion, with a 21 x 30 inches sheet size, a Littlejohn cylinder proofing press, cabinets of metal and wood type, and all the myriad objects that make up every letterpress print studio — including a substantial reference library of type, printing and graphic arts books. Some discrimination in the choice of types had to be exercised, which is perhaps regrettable now, in view of the large amount of unwanted type then coming on the market that was ultimately destined for scrap.

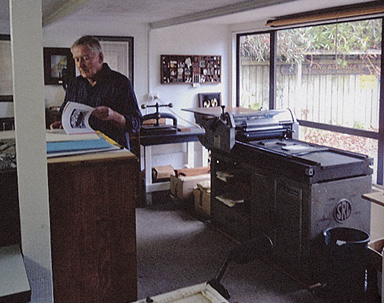

The Press’s output was not great in the years 1990-2000, because of the need to fit printing around other revenue producing work. By this time, the Albion had moved indoors, the wooden floor being reinforced from below. I worked mainly at night, with the disadvantage that artificial light is not very suitable for matching colours or picking up finer details. However, the Press has moved twice since then, and is now in a converted double garage with a glass wall letting in natural light.

As I have also been working as a printer/designer for the Holloway Press at the University of Auckland since 2001, an imprint that tends towards high-end fine print books, my own work now consciously tries to display a contemporary feel, though always there is the influence of years of print tradition, with rules that have stood the test of time. Certainly, working with equipment with such a provenance makes one aware of this.

The work produced consists of the usual private press small edition books, some set on a Linotype, some hand set, mostly in a number of colours and generally of non-traditional design, some involving experimental typography. The Press’s authors are mainly New Zealand poets and writers although, as a rule, publishing poets, who are usually struggling themselves, means that any financial return to the artisan cannot reflect the work involved. This seems to be a common experience among crafts people.

Printers must choose work that has some sort of resonance for them and the finished work must satisfy them. I have a strong interest in the design side, using letterpress as a vehicle for artistic expression. My interest in typography has led to experimentation with media which often include wood type. Many of my books are largely text, with some background decoration. Some cross the border into artists’ books, though still retaining strong relief print content.

One commercial Linotype supplier, Longley Printing, survives in Auckland, though I am not sure for how much longer. It has a good range — Janson, Granjon, Baskerville, plus the usual jobbing printers’ selection. But new processes in book production must now sway design thinking for letterpress printers. The photopolymer plate has opened up our world and might be called the salvation of letterpress. I have completed two books of substantial size, up to go pages, from these plates. Certainly the printer’s job is made a lot easier. Gone are the hours devoted to page make-up, the lifting and storing of heavy metal type formes and the subsequent dismantling and distribution of hand-set type, or the loading of used Linotype slugs into the car to return the metal to the typesetter.

By its nature, the Albion press allows for long lengths of paper to be passed through, feeding in from one end and out the other. A feed board is attached to either end of the bed so as to keep the paper off the rails. The scale of these sheets, up to eight feet in length, requires large lettering, so a good supply of wood type is needed. Printed sections governed by the print area of the press are set up and printed, then the following text section is set up and paper moved along into position. Register of follow-on sections is done with pencil marks on the paper and the bed of the press. Why a continuous sheet and not joined sections? The challenge, I guess. And, obviously, paper from rolls. To achieve the two colours, second colour letters are removed, inked separately then dropped back into position and one impression made. Large wood type formes need to be heavily inked, so that laying the sheets out to dry is a problem. Available floor space can be a determining factor for my print runs.

Also a ‘reverse’ letterpress printing system can be an aid to experimentation — the paper is laid on card on the bed of the press, the letters are separately inked, positioned face down and printed. No locking up is needed, and the letters can be positioned at any angle.

The interest in a technology from a previous age is now apparent in the attraction of letterpress for a younger computer literate generation. This is particularly so among a few astute young designers keen to understand the historical background of their computer fonts and the design procedures they have been taught, and at the same time to discover hands-on techniques requiring personal involvement. The future of letterpress is in their hands.

To date the Pear Tree Press has produced over 30 books, plus a substantial output of posters, broadsheets and other ephemera, with works being held in libraries and collections in New Zealand, Australia, England, USA and Canada.