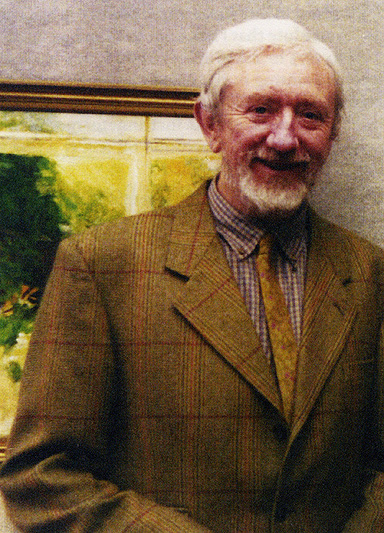

Nicholas Parry was well known to the book world on both sides of the Atlantic, where the output of the Tern Press has been admired and collected over many years. Even at the last Fine Press Book Fair in Oxford in November 2011, though obviously unwell, he was enjoying the company of printers from all over the world, all of whom recognised the very special character of his work, with that of his wife Mary, in the creation of their books. Over many years they had gone from selling books from their famous tandem bicycle to tours of the United States and exhibitions of their work in prestigious dealers’ shops and galleries.

Nicholas met Mary at art school, where they both studied painting and printmaking, and especially stone lithography. At first he painted and exhibited widely, while also working as a designer and film animator. He and Mary bought a press when Nicholas won a Welsh Arts Council painting competition, and in 1973 they created the Tern Press together. It was named after the river near their home in Market Drayton on the border between England and Wales.

They explored many of the techniques of printmaking to accompany a wide variety texts. They shared a passion for words, and their list of titles reads like an essential guide to English, indeed world, literature, spanning many centuries. Nicholas is widely quoted as saying that ‘our initial aims were to relate each subject to a relative set of materials, to think of the book as an overall work of art, rather like an opera, with a body (stage – props – paper – binding), intellect (thoughts – words – libretto), and feelings (music – colour – prints), to try, as in all art, to produce a form that lives and breathes. Thus our books are not conceived, designed, produced through process, but are perceived, arranged and produced through craft.’

Imagery was important to all their books, and there are many examples of wood or linocut, stone lithography and etching, and the choice of typefaces and their design became important too. A Ludlow typecaster was used for producing their texts, and they would work on this together. They created a typeface derived from a Roman inscription from the time of the emperor Hadrian that had been found near the Press, where the river Tern joins the Severn. Even as a student Nick had taken copies and rubbings from it and had admired ‘the sublime sense of space and movement which shifts constantly as the light changes’. A study of music for the lute also became a source for his own scripts used in some hand-written special books. Thus the publications of the Tern Press demonstrate a complete and integrated approach to all the component parts of the making of a book.

Nick was a passionate believer in communicating our literary heritage in the most beautiful way he could envisage, and his talents were not confined to the printed and illustrated page. He was a painter, and many of his books are also original paintings. Latterly, lithography directly from the stone was his most favoured technique and there are some books where he uses three colours; some are handcoloured within the lithographed drawing, all with great delicacy. Nick often spoke of the inspiration of colour and subject matter he continued to find in the Shropshire landscape. Indeed, he painted 22 frescoes for the Festival Drayton Centre which encompassed views of local streets, canals, bridges (especially one by Telford) and the surrounding landscape.

He was a musician who loved early music, and was an accomplished performer on the lute as well as a lively banjo player in a jazz band. Many of the books relate to musical subjects and there were drawings of musicians at a jazz festival they visited in France.

It is difficult not to write about Mary here because together they were the Tern Press and her skills were of equal importance to all they produced — and especially her bindings. So while celebrating the life of the partner who has died, we must also express our good wishes to Mary and their family, always of central importance to them, and hope that they will continue in their love of producing books.

Alan May

I first met Nick Parry at the Lute Society Summer School at Cheltenham, in 1972 or 1973. I was a newcomer both as a player and as an instrument builder, but he had attended previous schools. We discovered that we lived only a few miles from each other and that we had other interests besides early music in common. Both of us were working in art schools teaching printing and printmaking. But I was in need of lute lessons and Nick wanted a new tenor lute, so we agreed an arrangement whereby we made alternate fortnightly visits to each other’s house to play together, and at the same time I started on building his lute. The arrangement worked well, although I think I had the best of the deal, as Nick introduced me to a whole wealth of lute music of which I had previously had no knowledge. I am thinking in particular about the wonderful range of duet music that he showed me, as well as the hauntingly beautiful vihuela music of Luis de Milan and Luis de Narviez.

Nick’s interest in lute music extended to the baroque, but the eight-course lute that I had built for him had insufficient range, and in 1975 he asked me to build him a baroque lute based upon a painting in the Alte Pinakothek at Munich of ‘Lady tuning a lute’ by Hendryck van der Neer. He subsequently had the neck of this instrument modified and I heard him play the Bach Chaconne on it just a few weeks before he died.

In 1989 I joined the staff of the Department of Typography and Visual Communication at the University of Reading. A feature of the course there was that all students were expected to take part in intensive taught study courses during the Easter vacations in their second and final years. These included visits to northern Europe where the focus was on type design, and to Rome and Florence where inscriptional lettering was studied. In 1991 it was the turn of Rome and Florence, and the Parrys and Mays had a memorable ten days.

Nick and Mary’s interest in making and printing books led them eventually to look at the possibilities of casting their own type. In the early 1990s I located a Ludlow typecasting machine in Reading which Nick decided to buy. I am not sure now whether my find did them a good turn, though, as transporting and installing such a heavy machine in the cellar at St Mary’s Cottage proved to be not without incident.

Nick’s enthusiasm and determination to pursue his visual and musical talents come what may was an inspiration to all of us. He is greatly missed.

Nicholas ]ohn Pariy, artist and printer, born 2 March 1937, died 13 March 2012.