The Inward Laugh: Edward Bawden and His Circle by Malcolm Yorke. The Fleece Press, 2005. Published in an edition of 750 copies. Standard copies £262. One hundred special copies in a slipcase accompanied by four copper engravings printed by Tony Dyson, £432.

Edward Bawden: Editioned Prints by Jeremy Greenwood, with an introduction by Elspeth Moncrieff. The Wood Lea Press, 2005. Published in a standard edition of 450 copies in a slip case £125. Fifty-five special copies, bound in leather and in a cloth-covered solander with twelve of the Morte d’Arthur linocuts printed by the artist’s son, £445.

Books about Edward Bawden are rather like London buses in the pre- and post-Livingstone era — previously spasmodic (Richards 1946, Harling 1950, Bliss 1979, and McLean in 1989), and now bumper to bumper in Oxford Street (two books within three months in mid-2005). Not that Bawden would have been affected by the buses: Malcolm Yorke repeats the story of the new arrival at the Royal College of Art in 1922 being so bashful of contact with other people that he chose to walk everywhere. This was the man who, twenty years later, was to be torpedoed on board the SS Laconia, with a great loss of lives, survive in an open boat off Africa for five days in shark-infested waters, and rarely mention it afterwards, save one searing lithograph of survivors in a boat included in the otherwise jolly series for an anthology of Travellers’ Verse that he illustrated in 1946.

This threatens to take us on to the many enigmas of Edward Bawden, who took most of them to his grave in 1989, having demonstrated an astonishing versatility in a number of areas, and yet still being relatively unknown beyond a now-widening circle of admirers and those who have been influenced by his approach to design. Whether he skilfully created the enigmas in much the same way that he perfected his deafness to be a highly effective defence, or whether he was cast from birth to be, as one critic observed, a bystander outside normal society, rather like a foreign visitor watching a game of cricket for the first time without the benefit of explanation, is still an open question. Neither Yorke nor Moncrieff ever met Bawden, and so both have had to work with the witness of others who had, and the evidence of their own eyes in assessing his achievements. Moncrieff’s introductory essay to Jeremy Greenwood’s demonstration of all Bawden’s editioned prints makes a perceptive assessment of his work in the sphere of printmaking, bringing fresh insights while also recognising what he had done in kindred fields of murals, advertising, design, illustration and watercolours. Yorke, wisely not trying to update the biography by D. P. Bliss (although its unavailability in print is only to be regretted), sets out to discuss his life in a broader historical context using his extensive knowledge of other 20th-century British artists. This he does very well, and his research, particularly into the important years that Bawden spent as War Artist, gives the book additional value. He tackles the vexed question of whether there was a School of Great Bardfield artists sensitively, quoting adamant contemporary announcements by the eight members of the Great Bardfield Artists’ Association that there was not. Against that he rightly notes their widely held interest in depicting the English landscape, their common practice of technical innovation, of saying new things about old subjects, and ‘extending the landscape tradition rather than remaining complacently inside it’. Of the eight, four (Bawden and his three former students, Bernard Cheese, Sheila Robinson and Walter Hoyle) were very much in the William Morris tradition of working in various media and blurring the distinction between design and fine art. He also tellingly points out that during the two decades after 1950, during which British art was ‘buffeted by nineteen whirlwind fashions’ including Pop Art, Neo-Dada, Super-Realism and Abstact Expressionism, the Bardfield artists for the most part consciously continued with their figurative depiction of the natural world. It was more prosaic things like divorce and the natural movement of families to different parts of the country that caused the gradual dispersal of the community by 1970. Yorke’s approach, and an agreeable way of writing (Bawden’s nudes were as ‘lifeless as dummies’; Ravilious’s only Italian after three months in Florence was to be able to ask for the lavatory; Bawden, Ravilious, John Aldridge, John Nash, Cedric Morris and Kenneth Rowntree were all ‘set aside from the inbred squabbling art world in London, although they were aware of its factions from reviews, exhibitions and the common-room chat in the London colleges where they taught. At Gt Bardfield they were avid gardeners but not avant-gardeners’) carries the reader through 270 pages of fascinating material.

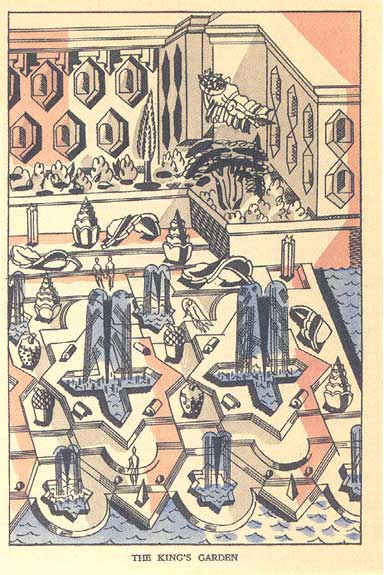

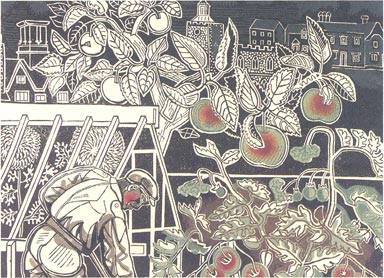

Both books, emanating from private presses in different parts of the country, were sufficiently aware of each other for Simon Lawrence’s Fleece Press to deliberately steer clear of Bawden’s prints in the 236 illustrations that are beautifully reproduced in the Circle book. To do this was something of a self-denying ordinance which could have cost the book dearly had he not so well compensated by unearthing much work not generally or easily to be seen before. Apart from a niggle about the captions sometimes using the abbreviation EB, and also not being indexed, the care that has gone into their choice and layout on the page is deserving of full praise. Jeremy Greenwood (The Wood Lea Press), felicitously served by Moncrieff’s 8,000-word introductory essay, reproduces all the editioned prints, and a few more as well, like engravings and pattern papers. All 200 are exceptionally well printed (both publishers using J. W. Northend Fine Print of Sheffield) and meticulously annotated with a commentary and reference to where they are publicly accessible. This part of the book obviously speaks for itself, and the versatility of Bawden, whether cutting in lino the fine architectural detail of the roof of Liverpool Street Station or delighting in the gory aspects of Morte d’Arthur (all 66 reproduced in reduced size), shines through. Just occasionally the layout of a page gives rise to more areas of white than one’s eye would perhaps wish to see, and again the lack of an index mars an otherwise thoroughly commendable book. It is the first time that such a comprehensive collection of work by what we can now fully comprehend as a master has been brought together. Bawden afidonados have every reason to be grateful that these two books enable a greater level of understanding than before.

Fleece Press

Denroyd Barn,

95 Denby Lane,

Upper Denby, Huddersfield HD8 8TZ

The Wood Lea Press

I Warren Hill Road

Woodbridge IPl2 4DT

Nigel Weaver was a hospital administrator and now helps run the Fry Art Gallery in Saffron Walden.