Editor’s note: This article is an excerpt from Thomas’s longer essay, Community as Art: the Story of Moving Parts Press. It’s being published here with the kind permission of the author and Felicia Rice, a printer, writer, publisher and the proprietor of Moving Parts Press.

As a reaction to America’s mass production and the consumer culture of the 1950s and ’60s, there was a resurgence of interest in fine craft in the early ’70s in forward-thinking locations like the San Francisco Bay Area and Santa Cruz, California. Art schools, including Oakland’s California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts), encouraged students to experiment with new materials and to work against ideas of preciousness in the object. San Francisco became the nexus of a broader cultural change, with the Bay Area being an important locus of activity for letterpress printing as early as the turn of the nineteenth century. The Grabhorn Press, which was established by brothers Edwin and Robert Grabhorn in San Francisco in 1920, influenced generations of fine presses, including the Arion Press in San Francisco, through the level of precision and craftsmanship maintained in its work. Sherwood Grover, who advised Felicia Rice during her studies, worked as the pressman for Grabhorn for thirty years. Fine printing and its master printers were a significant part of the cultural milieu of the Bay Area throughout the mid-twentieth century. Early encounters with fine printing through media coverage and proximity to David Lance Goines’s Berkeley print shop piqued Rice’s interest in letterpress printing. In it she found a quality of inking and an intimacy with the printed page that cannot be replicated in other mediums. Its unique beauty connects to a deep history several hundred years in the making.

Down the coast from San Francisco, the University of California, Santa Cruz was an important site for education in the fine craft of letterpress printing. As Carol Sauvion notes, “The extraordinary beauty of the northern California coastline, the back to the land movement, and the perception that anything was possible also contributed to setting the stage upon which the revival of letterpress printing took place.”(1) When Rice arrived in Santa Cruz in 1973, Jack Stauffacher, the renowned printer, typographer, and fine book press publisher from San Francisco, was teaching at UC Santa Cruz and serving as a Regents Professor for a year at Cowell College, the home of the Cowell Press. After Stauffacher completed his tenure, the college students had access to all of the tools available in the printshop he had established. A loose group of a dozen students taught each other, acting as a cohort in an environment that invited students with a range of skills and interests to participate and work together in the creation of books, broadsides, and prints. This laid the groundwork for a rising generation of students whose training at the Cowell Press served as the backdrop for prolific creative careers. Among the students were Gary Young, Tom Killion, Jim Faris, Greg Graalfs, Holly Downing, Tom Whitridge, and Rice.

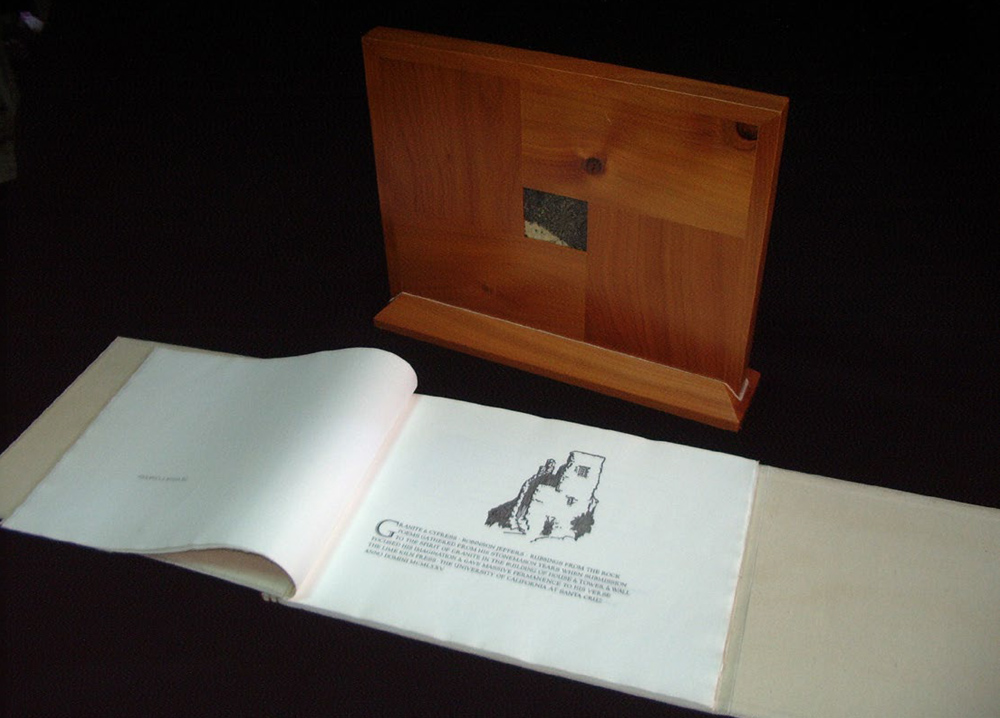

Robinson Jeffers, Granite & Cypress. Santa Cruz, California: The Lime Kiln Press, University of California at Santa Cruz, 1975. Photo: Felicia Rice

William Everson, the renowned poet and printer, was also teaching at UC Santa Cruz at this time and had established the Lime Kiln Press in the special collections department at the McHenry Library. With the help of a small group of students, he printed editions of his and others’ poetry on a nineteenth-century hand press. Everson, a former brother of the Dominican Order, maintained a near-monastic atmosphere in his classes, which Rice has described as “focused and silent, except for those moments when out of nowhere, he lifts a prayer, ‘Oh Jesus!’”(2) Everson also taught the class “The Birth of the Poet,” a celebrated class among UCSC alumni, as quoted in a poster for the class: “While not itself a rite of passage, the course of study will point to the crisis of consciousness in which vocation is revealed.”(3) His approach to Lime Kiln Press work with students was centered on collectively producing an edition of Granite & Cypress with poems by Robinson Jeffers (1975). The master-apprentice structure and dynamic became the primary model for Rice’s later teaching, and Everson’s meditations on vocation informed her commitment to Moving Parts Press.

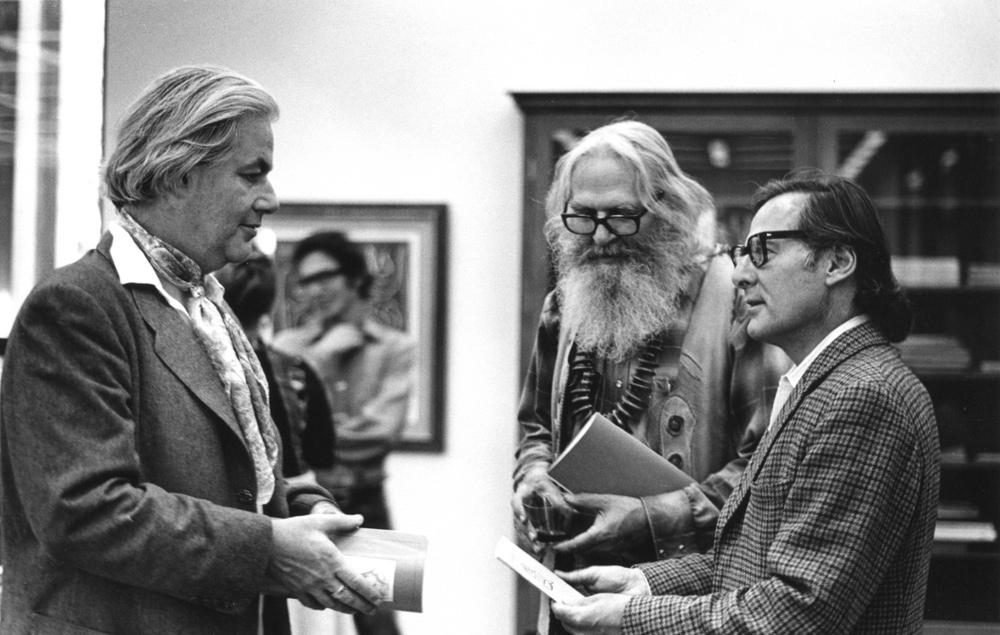

Founded in 1967, the UC Santa Cruz campus drew from Oxford University’s underlying philosophy of learning within small colleges, each with a different focus. This encouraged close dialogue between teachers and students. While enrolled at UCSC, Rice had the freedom to shape a rigorous course of study of the fine press book, alongside hands-on letterpress printing instruction from Stauffacher, Everson, and fellow students. Working with art historian and avid book collector Jasper Rose, letterpress printer Sherwood Grover, and art professor Hardy Hanson as advisors, she focused her studies on the history of the book and the impact of print technology on culture, society, and politics; examining closely the impact of revolutions in type and book design precipitated by the first books printed from moveable type in fifteenth century Europe.

Everson and Stauffacher’s ethos were grounded in precision: emphasizing the use of well-made materials, letterpress printing the book as exquisitely as possible, binding the finished piece beautifully, and placing strong importance on the design of the book. At that time and place, there were three compass points to the world of the fine press book: printer/publishers, book collectors, and book dealers. Fine printers who also acted as limited edition publishers joined a lineage dating back to the Arts and Crafts Movement in England and the US during the late nineteenth century, in which printers and their patrons—collectors with the help of book dealers—supported small private presses intent on using the tools of industry to create beautiful books.

Reception for Aristide Maillol exhibition, Special Collections, UCSC, 1976. L to R: Jasper Rose, William Everson, Jack Stauffacher. Photo: Andrew Neuhart

During the 1970s, printing was a male-dominated field. Some of its established figures held retrograde notions about what roles women could perform within it, and had limited perceptions of a woman’s ability to make substantive contributions. As a feminist, Rice pushed against these preconceptions. By April 1977, she was purchasing equipment with book binder Maureen Carey and had opened Moving Parts Press in a converted garage at 419 Maple Street in downtown Santa Cruz. Their acquisition of equipment took them to dark and dusty warehouses that stored the remains of the letterpress trade, tools no longer part of the economic mainstream that were being replaced by phototypesetting and offset lithography. The equipment they collected was at risk of being junked, making their acquisitions a rescue mission as much as a salvage hunt.

The name for this enterprise, Moving Parts Press, emerged the night Rice printed her first piece in the new shop, a broadside of a poem by Santa Cruz poet Ellen Bass. The broadside needed a colophon: the tailpiece that makes clear who, what, where, and when an edition is printed. A friend, Laura Danielson, was at the press with Rice, and they began volleying ideas in response to an image of a tractor printed at the bottom of the piece, starting with the phrase, “Printed movingly at . . . ,” and iterating from there, carrying forth the spirit of interconnection and collaboration to arrive at the name Moving Parts Press. At that point, the heart of the press’s mission was developing an audience for beautifully designed and letterpress printed everyday items ranging from business cards to books.

An alternative culture was growing in Santa Cruz, which had been a sleepy beach town and retirement community before the university was established. A generation of young people were creating a community based on their own set of values. They established small businesses in support of one another at a time when $50 (passed from one to the other) was enough to survive. This subculture also fostered the Santa Cruz Printers’ Chappel, a group of book arts practitioners established by George Kane that attracted many former UCSC students who had been involved at Cowell Press and decided to remain in Santa Cruz.(4) Members of the Chappel represented a wide variety of practices, including letterpress printing, bookbinding, paper marbling, paper making, calligraphy, and bookselling.

The Santa Cruz community fostered talent that was recognized within the region and beyond. For example, significant figures within the local writing community, like Bill Everson, Adrienne Rich, and James Houston, attracted numerous visiting writers, consistently bringing new voices into the scene and connecting it to a broader literary context. The small press movement was also beginning to grow, challenging New York as the center of the publishing world, and its gatekeeper. Small presses on the West Coast helped democratize the publishing world by seizing the means of production, publishing books themselves, and creating markets for their work. As part of the movement, a cohort of women-led and feminist small presses emerged, including Five Trees Press and Kelsey Street Press, alongside Moving Parts Press.

In the small city of Santa Cruz, at a certain moment in time, it was possible for Rice to be both printer and designer within a close community of craftspeople whose skills and expertise complemented her own, generating a unique momentum that proved to have a broader impact.

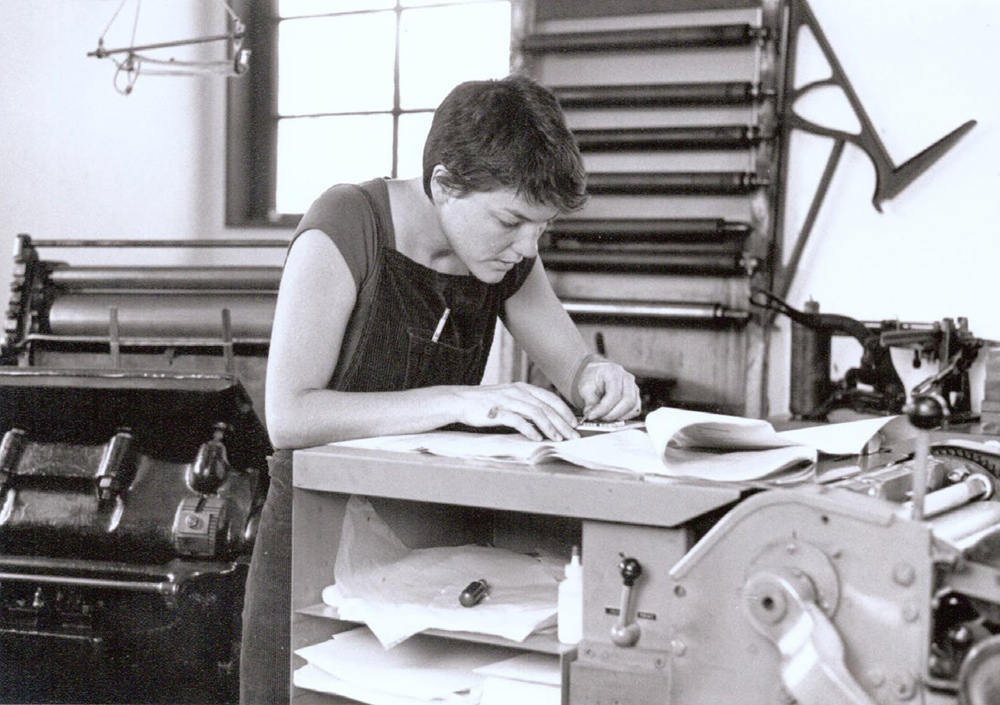

Felicia Rice at work in Moving Parts Press 1970s. Photo: Paul Stover

Felicia Rice at work in Moving Parts Press 1980s. Photo: Paul Stover

NOTES

1. Carol Sauvion, email message to Felicia Rice, July 29, 2022.

2. Felicia Rice, “Embrace,” unpublished performance text created in conjunction with Doc/UnDoc, 2014.

3. Ken Weisner, “Birth of a Poet: Selections,” Quarry West 32 (1995): 50.

4. For more on the Santa Cruz Printers’ Chappel and the Cowell Press, see Regional History Project, UCSC Library, Graalfs, G., & Reti, I. (2005). The Cowell Press and Its Legacy: 1973–2004. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0mz917dq.