Designed and printed by Aaron Cohick. Colorado Springs, CO: The Press at Colorado College, 2019. Double-sided accordion book with sewn-in sections. Clamshell box made by Further Other Book Works. • 90 pages, 12.5 × 8 in. (opens to 12.5 in. × 13 ft.) • The text is letterpress printed from photopolymer plates. The images are rubbings made directly from sidewalks and curbs. • Variable edition of 30: Twenty copies for sale plus ten artist’s proofs. • $1,500; out of print. • https://www.thepressatcoloradocollege.org/

Reading the fine press edition of Divya Victor’s Curb is an experience requiring various kinds of interactions. It challenges the reader in terms of its content and the physical act of reading it. Both the poetry, by Victor, and the design, by Aaron Cohick at The Press at Colorado College, grapple with the difficult topic of violence and various kinds of aggression toward South Asian Americans and migrants. The fine press book was the original format for the poems; Victor later published the same poetry, with additions, as a regular edition.

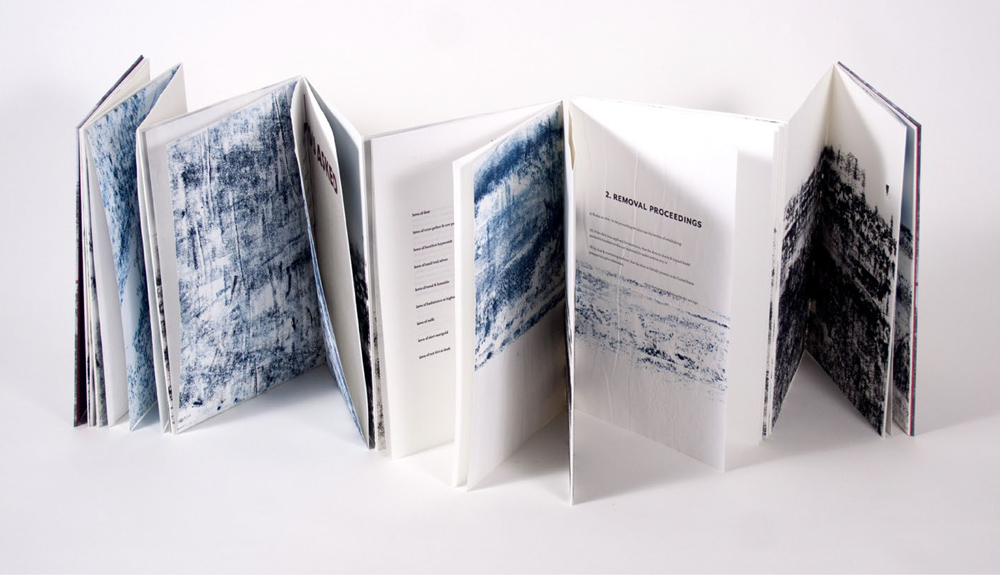

The character of the clamshell box (made by Further Other Books) mirrors the subject matter. Its gray color is crossed through by a line of dull red, perhaps for blood spilled. Within the book, the pages without text are covered in bold black and blue rubbings taken from sidewalks and curbs. The visual and physical textures of these rubbings make for a tactile, interactive experience. Sometimes, the poetry’s text is covered by a rubbing, making the words barely visible, as if their importance was overridden by the violence of the sidewalk.

Curb has an accordion binding that creates a feeling of discovery. Victor fills one side with a series of poems; flipping the book around, one finds a poem, “Frequency,” inspired by a case where Alka Sinha offered testimony against the court’s lenient response to the killing of her husband, Divyendu. Mostly describing the sounds surrounding Alka in the courtroom, the poem ends with the eerily cheerful voicemail greeting recorded by Divyendu and played by Alka in court. Victor had apparently conceived “Frequency” as the spine of the book, a choice that’s reflected in the book structure, with the poem backing many other poems on the other side.

The book’s other side begins with quotations related to sidewalks, streets, and boundaries. These are quickly followed by a list of names to whom the book is dedicated. I almost missed this list, however, because it is hidden under a foldout of a sidewalk rubbing. Victor mentioned wanting to recreate a map-like experience in the book, and that the challenge of reading, with its potential for misreadings, is part of the point of Curb’s form.

The poems that follow focus mostly on the murder of a few specific South Asian Americans and immigrants, with a short description of these people and the incidents alongside details about how unjustly their cases were handled. Victor also includes a quotation from the Immigration & Nationality Act. Coupled with the trial in “Frequency,” the ways in which prejudice and racism are part of and upheld by the law permeate much of the book.

The poems not dealing with murder still deal with loss, prejudice, microaggressions, violence, and the fear surrounding all of this in America. The first poem sets the framework for the rest of our reading. It is from a conversation between Victor and her mother in which her mother expresses her constant fear because “all of us are the same to all of them.” She’s referring to how in the US after 9/11, South Asians in America could not feel safe from being viewed as terrorists. Victor follows these words from her mother with, “as we pull my child / in a Radio Flyer wagon painted Cinnabar or Hemoglobin / dragging all that blood around in the afternoon . . .” This prepares us for the bloodshed in the following pages. Like the list of names, this poem is also hidden behind a foldout with sidewalk rubbings. With these two map-like foldouts in the beginning, Victor sets the course for the rest of the book.

It only makes sense that, like with the book’s box, the color of the text is black and maroon. Unsurprisingly, the red type calls our attention to certain significant parts of the text—geographic coordinates, specific words, and biographies—while simultaneously reminding us of the blood of the South Asian community members killed.

Victor’s use of geographic coordinates, often included at the top of the page, ties in well with the map-like foldouts, and it also helps to emphasize the importance of space in Curb. As with the book title and the rubbings, the creators of Curb constantly remind readers of the streets where these events took place, forcing us to remember the location by stamping the poems with coordinates. The focus on spatial geography creates a general sense of the terror surrounding public spaces for South Asian Americans and immigrants. It also forms a memorial for specific people who have died from racism by tying the incident to a certain place, devising yet another way to remember the person and event.

The poems in Curb often challenge the reader, especially a reader who does not regularly read poetry, like me. Sentences are broken apart. Punctuation is missing. Additionally, as someone who does not read South Asian languages, I found that the occasional interspersing of non-English words among English words presented another barrier. But ultimately, the use of many languages mirrors the multilingual environment of the US, and specifically of the South Asian community. Furthermore, some of the poems tackle the challenges that immigrants may face because of the way that language and literacy is wielded by those in power.

Thanks to the colophon, we learn even more about the process of producing the book. For example, there is a layer of ink printed on the cover title for each person to whom the book is dedicated. Similarly, the red text was overprinted with gray multiple times to match the number of these people (which explains why the red is darker and less vivid). Even while the reader might not automatically know that this is how Curb was made, these acts show the tribute that Victor and Cohick pay to these victims of post-9/11 prejudice.

Curb, particularly this edition of it, has the potential to challenge its readers in a variety of ways—thematically, physically, linguistically—but in that challenge is its purpose. It makes readers want to revisit it, to understand more fully the complexities of the book and its subject. It is certainly an impactful memorial to the South Asian people who have suffered various and often violent injustices in the United States.

SOURCES

Sur, Sanchari. “Coalition in the Imaginary: A Conversation with Divya Victor.” Asian American Writers’ Workshop, October 7, 2021, https://aaww.org/coalition-in-the -imaginary-a-conversation-with-divya-victor/.

Victor, Divya. “Aaron Cohick & Divya Victor, ‘Curb.’” The MCBA Prize, Minnesota Center for Book Arts, September 17, 2020, https://mcbaprize.org/aaron-cohick-divya-victor-curb/.