‘What needs to be remembered is that this is the largest exhibition of contemporary British Private Presses ever to be held’, wrote the art critic Terence Mullaly in the Daily Telegraph on 29 November 1976. He was reviewing the exhibition to celebrate the five-hundredth anniversary of England’s first printer, William Caxton, whose Press was set up in Westminster in 1476. These comments were echoed by several reviewers and, looking back after 43 years, they could well be repeated today, since the sheer size of the exhibition, with nearly 800 items on display, has never been surpassed in this field.

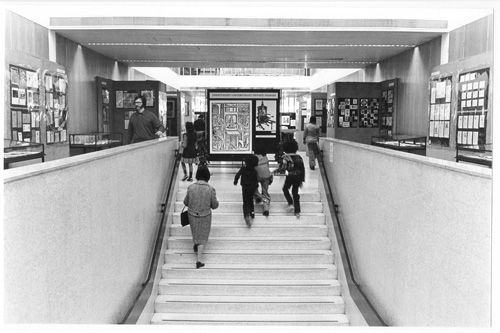

The quincentenary of England’s first printer was marked by a number of celebratory events, including lectures and conferences, as well as a major exhibition at the British Library, several new biographies of Caxton and a set of four commemorative stamps issued by Royal Mail. The London Borough of Camden’s contribution was to be an exhibition of contemporary private presses, to be held from December 1976 to January 1977 in the Central Library at Swiss Cottage. Camden was very proud of its ‘architectural landmark building’, designed by Basil Spence in 1964, and judged to be an icon of modernist architecture. It provided a vast exhibition space on its first-floor atrium: a most prestigious showplace for printers whose work was not often enough seen, even by collectors of private press books, let alone the general public.

The exhibition was organised and curated by the artist and printer Ian Mortimer, whose own Press, I M Imprimit, had been started just six years previously. Camden’s plans, however, nearly foundered. A letter from Frank Cole, Camden’s Director of Libraries and Arts, inviting Mortimer to organise an exhibition of ‘work from private printing presses operating at the present time’ as part of the Caxton celebrations, was sent in March 1976 but, although Mortimer’s Press and studio were barely 300 yards from the Library, the letter was sent to the wrong address and so never received.

After this inauspicious start, the Director wrote a second letter, dated 5 August – five months later. It was very succinct: ‘As I have not heard from you I presume that you are not interested in this scheme; I would like to confirm this as we now have a possible alternative for Swiss Cottage at this time. I regret that the printing presses exhibition does not seem to have raised your interest…’ Mortimer was horrified to learn what a wonderful opportunity was about to be lost, and immediately responded with urgency and enthusiasm.

This led to a meeting with Deborah Lambert, Camden’s Senior Arts Assistant, to discuss whether, in spite of the loss of the six months’ preparation period, it might yet be possible to put together an exhibition in time for the current Caxton celebrations. It was evident that Deborah, who had suggested the idea of such an exhibition in the first place, was very enthusiastic and keen that it should still take place if at all possible.

Deborah is the youngest child of Jack Lambert, then Literary and Arts Editor and later Asssociate Editor of the Sunday Times. After Camden, she worked at Christie’s, subsequently appearing as an expert on the Antiques Road Show, and becoming the curator of the Schroder Collection of Renaissance Silver, from which she has now retired. When they met again recently Mortimer asked her how the idea of the exhibition came about, but the only clue was a Sally Long, who was named in Frank Cole’s first letter (the one that did not arrive) as having put forward Mortimer’s name as a possible organiser of a suitable exhibition for the forthcoming Caxton year. Neither of them could remember any more details.

Camden Council had (and has) a track record of support for craft printing, printmaking and the graphic arts in the borough, particularly through the well-established Camden Arts Centre. Mortimer’s earlier participation in a Camden Printmakers exhibition was one result of this. Various local artists knew about his printing activities, including perhaps the mysterious Sally Long.

Camden agreed that at least six to eight Presses would be needed to make a worthwhile display in the large exhibition space available, and that the ones chosen should be working in the Caxton tradition: in other words, setting the type and printing the work themselves by letterpress. But the planned date for the show was now barely two months away. In the days before organisations like the Fine Press Book Association and the Oxford Guild had come into being, and long before the internet and email, there was no easily accessible list of possible contributors. And not a single Press had yet been approached.

The exhibition opening on 2 December 1976 with, left to right, Ian Mortimer, Douglas Cleverdon and the Mayor of Camden.

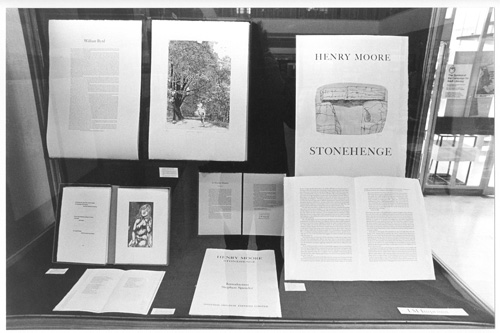

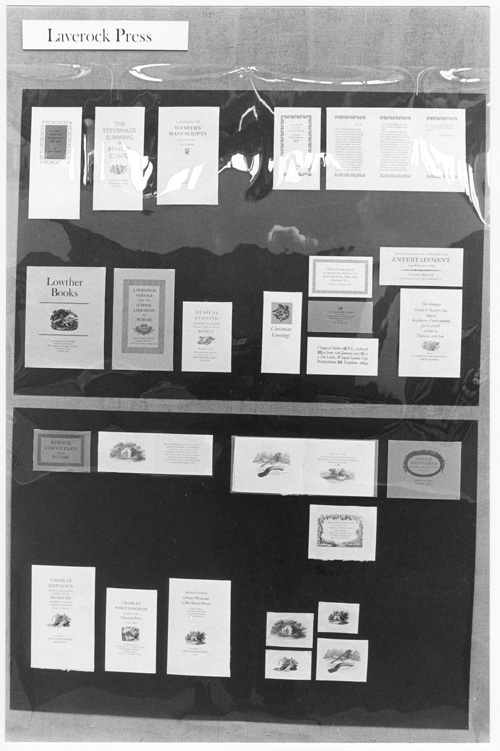

Since setting up his own workshop, Ian Mortimer had discovered the St Bride Printing Library and the Printing Historical Society, but he himself knew barely a handful of printers. His growing friendship with David Chambers, a passionate collector of private press books who knew and corresponded with all the active Presses large and small, enabled a start to be made. David suggested that a day going through his own collection could provide a list of possible contributors. As every collector knows, there is much more to a private press’s output than books. These were of course to be the main focus of the exhibition, but it is in the printing of announcements and prospectuses for forthcoming editions, broadsides, posters and leaflets, as well as smaller items such as address cards, invitations, letterheads – the often throw-away items that form part of printers’ day-to-day work – that Presses often reveal the riches of their typographic skill and imagination. It was clear that a selection of such ephemera from each Press must also be included if at all possible.

Mortimer accordingly wrote to some 20 Presses, inviting them to participate. The letter dated 5 September was headed `Fifteen Private Presses’, a number dreamed up in the hope of persuading the more established printers that they would be participating in an already well organised exhibition of a reasonable size. In it he wrote `I am very keen to show ephemera as well as books from the Presses, and posters, leaflets and prospectuses etc. are very welcome.’ Contributions needed to be delivered by 5 October – just a month away.

The responses were, thankfully, both swift and positive. Not a single Press declined. It became evident that the exhibition was going to be far more substantial than anyone had dared to hope, with some of England’s oldest established workshops, Stanbrook Abbey (1876), Rampant Lions (1929) and Stourton Press (for which Eric Gill had designed his Aries typeface in 1934) agreeing to take part.

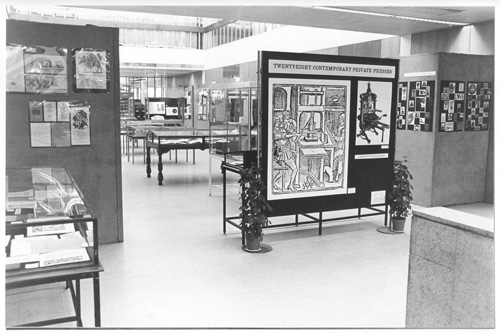

As more and more replies came in, the participants’ contributions started arriving, and the final count rose to 28, it was apparent that the display resources of the Library were insufficient. Deborah and her assistant were forced to organise and collect a mixed array of glass display cases and stands hastily borrowed from other London museums, including the Victoria & Albert and the Horniman. The decision had by then been made to show every item that each Press was willing to loan. The result was an overwhelming collection of ephemera, hardly any of which had been shown in public before, and more than enough to cover the walls and display stands surrounding the glass cases. A team of volunteers, including some of the printers themselves, arranged and mounted them on large sheets of dark brown card, using photo corners. The finished sheets were covered with clear cellophane to ensure the exhibits’ safe return.

With so little time available, advance publicity was limited to a hastily put together press handout by Camden Libraries, while Mortimer designed and printed an invitation for the opening night, and approached Douglas Cleverdon, who generously agreed to open the show. Cleverdon was a BBC radio producer who in Bristol before the war had published fine books with contributions by Eric Gill and David Jones, and was now the publisher of Clover Hill Editions.

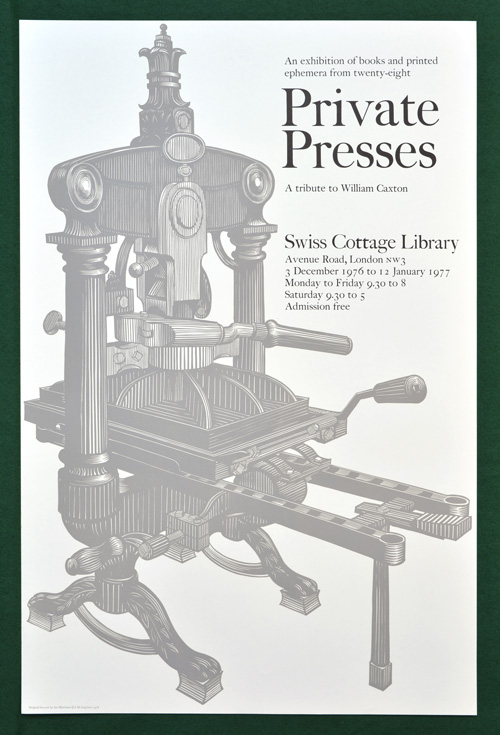

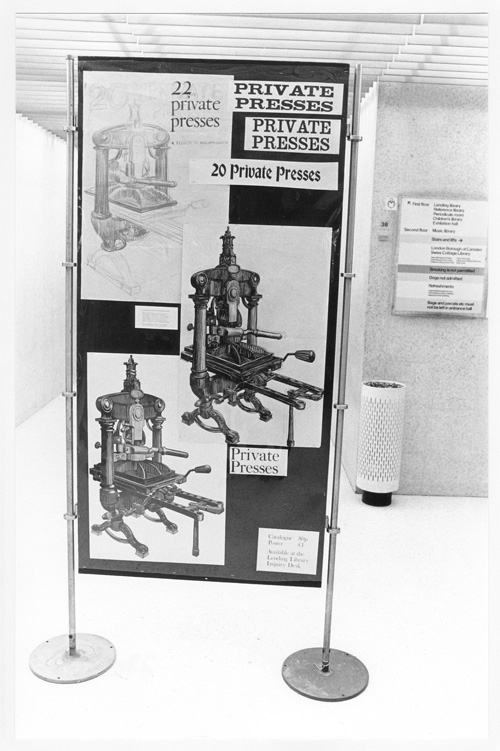

Notwithstanding the limited finances available, and the next to impossible deadline, Mortimer was determined to provide a large and eye-catching poster, the printing of which would after all be in his own hands. He had started sketching ideas for the image, a linocut of an Albion press to fill a double-crown sheet, as soon as the exhibition was agreed. The final poster, printed from his original lino block with text in foundry Caslon, has become a collector’s item – it can be seen on the wall of many printers’ workshops to this day. Some of the full-size sketch layouts, showing the title of the exhibition changing almost day by day as the number of Presses taking part increased, were exhibited in the show as an amusing comment on the hectic pace of the event’s preparations. For the entrance to the exhibition, the sixteenth-century woodcut by Jocodus Badius Ascensius of a wooden common press in use was photographically enlarged to provide an enticing `draw’, placed alongside a black-and-white proof of Mortimer’s linocut of the Albion for the poster.

Replying to Mortimer’s first letter, Rigby Graham of the Cog Press wrote `I hope you can manage a decent catalogue. It is all that remains when the show is over.’ The Library’s initial budget did not even mention a catalogue, and there was virtually no time to put one together. However, in the event Camden did agree to pay for a simple booklet, and luckily another friend, Sotheby’s private press book expert Michael Heseltine, came to the rescue. As the books and ephemera piled up and the deadline approached, Michael wrote the introduction, compiled the information note about each Press and catalogued all of the 178 books. It was quite impossible to catalogue, let alone illustrate, the over 600 pieces of ephemera in the show. Photography and illustrations were out of the question on grounds of time and expense.

So it was rewarding to discover recently, in I M Imprimit’s archive, together with complete files of correspondence and costs for the exhibition, a collection of long-forgotten installation photographs. They were taken by an unknown professional photographer, presumably employed by Camden Libraries, and provide what seems to be the only surviving evidence of the exhibition’s scale and impact. Though not a complete record, the photographs do convey some of the excitement of almost 800 hand printed items in one space, most of them on show for the first time. Six of the photographs are reproduced with this article.

In January 1977 the show was over, and the exhibits, mostly uncatalogued and unrecorded, were returned to their printers. But that was not quite the end. Late in 1976 Charlene Garry, owner of the Basilisk Press, arranged to take over the lease of the building in England’s Lane, near Swiss Cottage, in which Basilisk had its offices. Charlene wanted the ground floor shop to display Basilisk Press publications, but her three editions, however sumptuous, would not fill the shop. Visiting the Swiss Cottage Library show, and enthralled by the variety and exuberance of contemporary printing, hardly any of which could be seen elsewhere, she wrote to all 28 of the Presses, whose addresses had been handily included in the catalogue, offering them a display in the new shop. Most of them sent stock, the word got round and even Presses not included in the show made an appearance in England’s Lane. The Basilisk Bookshop is another story, but it would not have existed without Twenty-eight Private Presses at Swiss Cottage in 1976.

With acknowledgement to Ian Mortimer