The artists’ book movement in the U.S., which initially took off in the 1970s, had by 2000 become something of a cottage industry, with book arts centers throughout the country teaching hands-on classes on how to create artists’ books. These workshops led to a proliferation of second- and thirdgeneration teachers of book arts and an inevitable dilution of the craft skills involved, so that what remained had little more aesthetic cachet than the scrapbooking craze.

The movement had its beginnings with a few individuals (conceptual artists Dieter Roth, Hansjörg Mayer, and Ed Ruscha immediately come to mind), but in the area of structural experiment and invention only one person seems to have been markedly influential (albeit seriously ignored): Hedi Kyle. Kyle has not written or published much about her work, her innovations, or her ideas, but was a teacher at Ox-Bow in Michigan for decades, is a member of the faculty of the Philadelphia University of the Arts, and has toured the U.S. giving workshops on the bookmaking arts. Her former students exchange PDFs and photocopies of her diagrams as if they were tablets from on high. In 1993 the Center for Book Arts in New York mounted an exhibition of works by 20 contemporary artists influenced by her teaching.

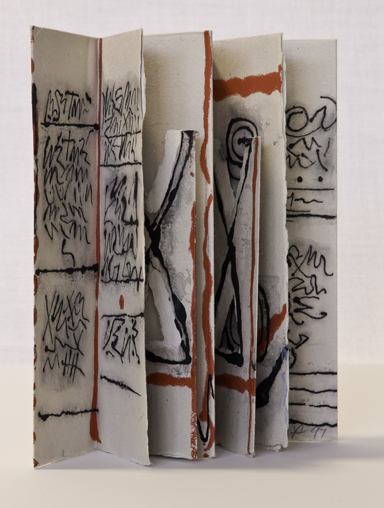

It’s easy to make a case for Kyle as the most influential book artist of the 70s and 80s. Her unique and elegant ideas have spread into the everyday repertoire of other teachers and can be traced through most contemporary books that break away from the codex format. Today accordion spines and flag books are almost commonplace. Many of her ideas sprang from three decades working as a conservator at the American Philosophical Library in Philadelphia (she retired in 2002). Though she seldom receives credit, you can find her innovations replicated in works like Making Handmade Books (Lark Crafts, 2011). She is not short of inspiration and believes strongly in sharing it with others.

I called her when the iPad first appeared on the market. The iPad case has an articulated plastic cover that folds back to create a stand: a classic Hedi Kyle concept. She laughed, perhaps amused to think that something plainly destined to be wildly successful might actually have come from one of her structural innovations. Intrigued by her resourcefulness, which is seemingly endless, as well as our mutual interest in historical applications of structural ideas (like the paper scourge that used to be on display in the British Library when it was in Bloomsbury), I interviewed her by phone in 2011 to find out more about her life, her background, and her work.

Kyle was born in 1937 in what was then the republic of Poland. Entering first grade in 1944, she was rapped on the knuckles for writing with her left hand; her grandfather taught her to use her right instead, and so she became ambidextrous. With World War II raging around her it was a difficult time. She recalls, “My father was in the war, and my mother was alone with four small children and my grandmother. We took the last train out of Poland and it was unbelievable — there were so many people. We lost my youngest brother, but then we found him again. He was actually under the train at one point! It was horrible.

“But then we went to a very beautiful place near Weimar. Later the Russians came and we had to move again. But for a few months that was heaven.

“I had an aunt there who was a famous pianist — there was everything there.” But in the surrounding countryside there was nothing. She attended a village school in the morning. As she tells it, she had a black and white fur coat that her grandmother turned inside-out, so only the brown lining would show, to make her look less conspicuous. Her grandmother warned her, “If you hear the deep fliers, get flat and crawl under the bushes!”

The “deep fliers” were Russian fighter planes that flew low and strafed civilians.

By the time she was eight, the Americans had arrived. They camped in a local park and gave the kids peanut butter, chocolate bars, and Chiclets, but then they left and the Russians took over the occupation. The family continued to move frequently till, in 1946, her father at long last returned from the war. As a marine biologist, he managed to get a job on the island of Borkum in the North Sea, the westernmost of the Frisian archipelago, immediately north of the Dutch province of Groningen.

Living on an island had a marked effect on young Hedi. She read everything she could get her hands on, including a few of her parents’ books that were supposed to be offlimits. She remembers reading Jack London, John Steinbeck, and George Sand, as well as Reader’s Digest, which they looked forward to receiving in the mail.

During the day she would go to the beach and make things out of driftwood and the flotsam that washed ashore.

After high school she went to an art school in Wiesbaden that was modeled after the Bauhaus. The director was a former student of Johannes Itten, and she spent a lot of time doing Bauhaus-related color studies. She loved drawing plants and made primitive books that were imitations of herbals. I asked her if she also pressed plants, and she said she liked that aspect of books, that you could also put things in them.

She went on, “I studied book illustration and graphic design, but I never made a book. I just designed books — you know, covers, typography, illustrations … and then we went to Offenbach [a city near Frankfurt] and they had a bookbindery where they would bind the books. And I was so blasé and I thought I was not interested in that kind of thing, like a lot of people: the book is useful for keeping information but as nothing else.”

At the time she graduated a lot of large American advertising agencies had opened up in Germany, and she managed to latch on with J. Walter Thompson as a commercial artist in Frankfurt. Her job was to accompany the art director to meetings and create storyboards of whatever they talked about. She produced quick sketches that would eventually be used for making television commercials for Lux soap, Philadelphia cream cheese, and so on.

All through her teen years Kyle had enjoyed a remarkable freedom. She bicycled and hitchhiked through France, Italy, Greece, and Turkey, and when she turned 21 she took her savings and went to Greece to spend a year painting. “You know, if you don’t have money you have to sleep outside, and so you need to go somewhere warm. The first time I went to Greece was in the late 50s. Then it was so unbelievable. I loved it totally, and they had hardly seen any German tourists, certainly no hitchhikers.

“I knew Greece quite well and so when I went there for a year I went to Crete, to a village called Lindos, which was like a small artists’ colony. I had friends there, it was really wonderful.”

While she loves teaching, Kyle admits to having spread herself a bit too thin, mostly on account of her multifold interests. “I get easily excited about [one thing] and then I follow it until something else comes along and takes its place. I am also very inspired by my husband — he has an archive on book arts. He collects everything he thinks I could be inspired by.” Her husband is in fact a major collector, stockpiling images and data for sale or rental. He began with a film archive in Germany, acquiring stills, posters, and lobby cards that he has subsequently rented out to magazines and other media clients.

So Kyle is constantly stimulated. I ask her about her work and whether it gets into private collections. “I don’t really make that many books. A lot of things never really get out, because I am more or less amusing myself. Since I retired — well, not completely … the first year I did a lot of workshops, and right now I am still teaching, and I love that so much.”

But the traveling involved in giving workshops proved too demanding for her to continue with them. Not to mention the significant differences between a one-off workshop, which meets just a single time, and an ongoing class of students.

“Sometimes you develop a following of some people, like groupies who come to all of your workshops, [but mainly] you develop via correspondence and friendship. But with the students it’s so different, because over two years you have them every week and you build up kind of a repertoire. That’s so much more rewarding.”

I wanted to know how she got into structural processes and where her craft skills came from. A lot of people with a traditional craft background never really delve into it, much less think about what could ultimately come out of it.

Kyle studied with Laura Young in New York in the 70s. “She had all these students that were very loyal, and they were all making boxes and making books, and the minute I got in the shop I thought, ‘This can be changed: why do you have to cover the spine?’ I questioned everything. I drove her crazy, but at the same time, she had a lot of patience and she was somewhat interested in this, and so she took me on. I learned all the basics from her, but I questioned all the other stuff, and she disagreed with me and we had arguments.”

She got into teaching accidentally, through meeting Richard Minsky, whom she describes as one of “the most notorious people in the book arts.” He had submitted a book to the Guild of Bookworkers show. It was a copy of Audubon’s Birds of America where he had stuck a pheasant’s wing onto a black leather binding. Guild members didn’t want to display it but Kyle insisted: “This is not a juried show, you have to show it!” When she met Minsky he immediately offered her a job teaching at the Center for Book Arts in New York. She told him she didn’t know anything about teaching, but he persisted nonetheless. When she informed Young about the offer, the cigarette fell from her mouth!

She conducted classes in traditional binding and practiced her craft skills late into the night so she could teach more effectively. Subsequently she taught workshops at PBI (Paper & Book Intensive), then at Cooper Union in New York City, until she moved to Philadelphia to work as a conservator. Then, in a fortuitous turn in 1987, the chair of the printmaking department at the Philadelphia University of the Arts took her out to lunch and invited her to teach. A few years after that, Ed Colker — then university provost — who had also been at Cooper Union and developed a bookmaking curriculum there, inaugurated the first graduate book arts program at Philadelphia Arts.

I asked Kyle about inspiration and she said she likes forgotten things. That’s why she enjoyed working as a conservator, because she would be in the stacks exploring and suddenly something not even cataloged in the collection would turn up.

“Yes, you are hoping for it. You go out there and you find it. You find great stuff. And at the time when I first started conservation … they have come a long way, but mostly people like these fancy bindings, these amazing tooled things and this and that, but I always was a promoter of the simple thing, of the old thing, and the falling-down thing that reveals itself, where you can see through layers.”

But the ingenuities of structure can easily get lost if too much of the focus is on decoration or content. She admits she likes neglected books or those that have been used carelessly.

“I have a whole collection of books that I either found on the street or at flea markets, or from people throwing out books, or even [at] auctions, but books that people have collected, have repaired in their own totally unskilled way, and have also used beyond what they were supposed to be used for.

“Just recently my friend and colleague Julia Miller — who was a conservator at Michigan, Ann Arbor — brought out this book, Books Will Speak Plain: A Handbook for Identifying and Describing Historical Bindings [Legacy Press, 2010], and it is exactly what I like and what I was inspired by, and what a lot of us, a lot of the early Ox-Bow people who were looking at these books, were inspired by: where you can see how they were constructed, how innovative the people were who bound them, the materials they used and everything. Really revealing.”

But she regrets that so many people tend to jump on the bandwagon, and suddenly everyone is imitating the old structures, which transforms the processes quickly from innovation to cliche, and so you have to move on. “We have also the other thing, which is supermodern and contemporary, and I have to say I like that too. I sometimes want to make a book that doesn’t have any of this old stuff at all, that is made out of completely new materials that we only know now, like Tyvek and plastic and that kind of thing.”

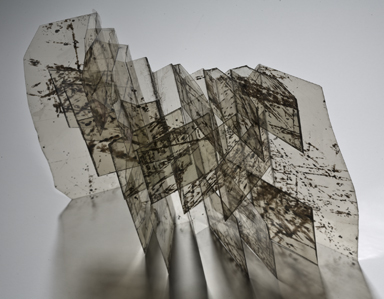

I mention how her structures have been mined for gimmicks and she tells me about a woman in the UK who is selling instructions for one of Kyle’s structures online. She complains that even though the woman is selling the diagram, she’s still hasn’t got it right! But, she says, when you teach you are giving stuff away, which means it can’t be copyrighted. At that point I admit to having taught her structures to fifth-grade book classes in public schools. She says she doesn’t mind, that she has plenty of other ideas and has been happy with her work, which is both stimulating and satisfying. She never “editions” anything because she doesn’t have the patience, but would rather go ahead and try something new. Though now with scanners and laser printers, she says, it’s been possible for her to make more than one copy of a book — like “Soap Opera,” her accordion book on translucent paper, which exploits the transparency of the last sliver of a bar of soap that has become too small to use. The book currently exists as an edition of seven.

Going back to the traditional orihon structure, and to the accordions and other folds that characterize her work, I ask her about Japanese aesthetics. She agrees they were the source of her initial inspiration. She prefers simplicity, the transparency of structure, to leather bindings with gold tooling.

Finally I ask about “gratuitous structure,” the idea of making books simply for their structural aspects, with little or no attention paid to what is literally inside them. The aesthetic of the book becomes an end in itself, a statement about sewing or binding, and the very notion of an independent, detachable meaning that is not — somehow — related to the formal structure becomes an irrelevancy. In other words, does “content,” so-called, actually matter?

She says that because she has always been so highly invested in structure she used not to pay much attention to content. But that is not the case anymore. “I really just don’t want blank books. To me that is a missed opportunity. But there’s always content now.”