Heteroglossia is a big word, and at 47cm high and 37cm wide (74cm when open), this is a very big book. There is something in a name. The term ‘Heteroglossia’ is defined by the artist as ‘the coexistence of multiple fields, relations and voices within a given language’. If you consider book arts a minor form, Heteroglossia is going to challenge that perception. It is a distillation of histories and archaeologies, sustained within the monumental medium at its core: lithography.

Serena Smith has long been known as an accomplished lithographer and teacher. Her technical expertise has served not only her own work, but that of a long list of artists, including Paula Rego, Ken Kiff and Bernard Dunstan. For many years she was Stanley Jones’s closest and most trusted assistant at the Curwen Studio, the artistic offspring of the Curwen Press, founded by Harold Curwen and Oliver Simon after the First World War. The Curwen Studio’s genesis was influenced by founding director

Stanley Jones’s post-graduate experience working in Paris, lending artists (Picasso amongst them) the facilities and expertise to produce their own limited-edition prints. In 1958 Jones was prised reluctantly away from the dynamic world of European modernism, by charismatic art entrepreneur Robert Erskine, to set up Curwen Studio in London. Jones brought the European outlook with him, and a strong ethos toward the democratisation of imagery. He worked with artists as diverse as Henry Moore, Man Ray, Glyn Boyd Harte and John Lennon, who wanted to work with ‘the give-and-take of a medium that could be permitted to develop a life of its own’. (Alan Powers, Art and Print: The Curwen Story, Tate Publishing, 2008, p. 108.)

In 1989, Curwen Studio moved out of London to Chilford Hall in Cambridgeshire, with Serena (then Serena Castle) and Stanley as the only lithographers. Serena had followed her art-school training by working at the Studio, initially as an administrator. She quickly became an accomplished lithographer. Artists wishing to realise an image with precision, sensitivity to exposure, and subtleties of texture and definition, found in her and Stanley the dream team. They worked together until 2011, when circumstances forced a move.

Since then, Serena has been based at Leicester Print Studio, where she has increased her teaching role, and dedicated more time to her own work. Her interest in the history of lithography has deepened into philosophy, and Heteroglossia, while a standalone work, is also embedded into her recently completed PhD.

It is not the first of her big books. It follows Ekphrasis, which examines bark and wood from the area where she lives, navigating between the site of her local woodland, its traces and debris, and that of her lithographic practice. Digging deeper into the studio, Heteroglossia is an exposition of the materials of lithography. At its heart is a series of images that bear relation to its earliest uses: 19th-century medical texts, especially the work of Robert Carswell (1793–1857) and Joseph Maclise (1815–1880). Smith’s aim with this book is ‘to bear witness to the embedded presence of lives that shaped, and continue to be shaped by, the practices of stone lithography’.

Heteroglossia is bound in a washed-red cloth, with titles and text throughout and on the cover in burnt sienna and black, colours constituent in the text. Endpapers are plain black, and the book paper (Simili Japon, 225gsm) is thick and smooth, almost like skin. The pages and endpapers are sewn. The text is produced digitally and printed on the 1930s Hunter Penrose Imperial hand-offset proofing press at Leicester Print Workshop, using photolithography plates.

There is an introduction, seven chapters and a bibliography, with full-page lithographs interposed within and at each end of the text. Each chapter deals with a different element of lithography: ‘Rocks and Stones’, ‘Elemental Dust’, ‘Sacrificial Inscriptions’, ‘Viscous Gifts’, ‘Toxic Agents’, ‘Audible Membranes’, ‘Ink and Skin’. Delicately exegetic, they tell of each substance that is used, from calcium carbonate (‘the crystalline purity of Iceland spar’) through soot (for Lamp Black, ‘the smoking gun of melting glaciers’) to human and animal sacrifices necessary to produce soap, wax, tallow, shellac, neat’s-foot oil and gum Arabic. The ink-rollers’ ‘velvet softness’ demands the skin of a very young calf. Those same rollers, when pulled from the inking slab, make a sound called a ‘kiss’. Toxicity is refined by poetry (‘A resinous scent pervades artisanal air…a volatile liquor and a woodland spirit’). And some ingredients are life-supporting: linseed oil, derived from flax, the seeds of which are anti-inflammatory and benefit intestinal health; pumice, when it floats in water.

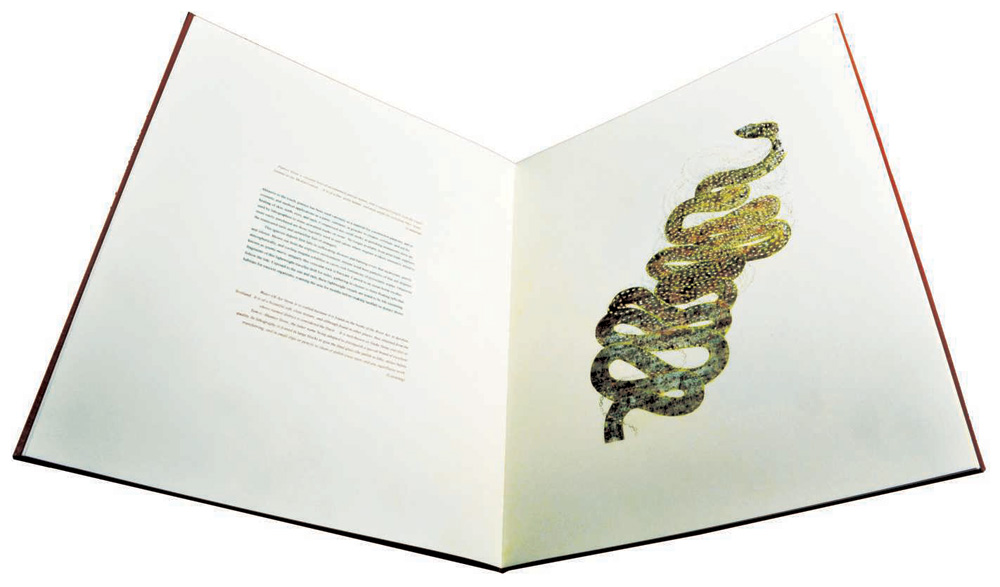

Each chapter has space within it and around it. The images which unfold alongside the text are visually related to structures and organs within the body: circles (like planetary orbs), ovoids, chains with beads; curling, serpentine forms, sometimes tubular, octopoidal, floating free against the muted background produced by the stone. There is an almost silken quality, like membrane. Chain structures are delicate, like connective tissue. Colours are pale earth, sometimes denser, especially in the serpentine shapes, while others are thin and balletic (‘Audible Membranes’). A light, strong yellow can define edge or infill a shape, and there is an occasional, fragile blue. The images vary in their hold on the page, sometimes sharp-edged, sometimes as though seen through fluid, reflecting the critical relationship of solid stone to surface fluid in the lithographic process.

Our unavoidable complicity in cruelty and exploitation, just by living the lives that we do, is laid bare, but without sensation or politicisation. There is cross-referencing throughout the book between human (and animal) bodies and the substances described. As the intriguingly designated Professor of Inhuman Geography, Kathryn Yusoff, is quoted as saying, we are totally involved with geology and minerals, both as extractors and users, and in our constitution. (Stardust!)

Artist’s books are at their best when they deepen and complicate the relationship between image and word. An artist’s book is essentially a made thing, where the relationship between text and images causes each to accrue meaning. Far from illustrations, these images are visual embodiments of the ideas and histories that are its subject.

Serena Smith’s work stands on an almost perfect trivet of tension between academia, art and science, and art and technology. She has become increasingly reflexive about her making process, and drawn to words that revert, like ‘Heteroglossia’, to Greek origins of scientific study and philosophy; what she calls ‘genealogies of knowledge that inform the artisan practices of lithography’. The homogeneity of art, history, language, science and technology in this book is reminiscent of Enlightenment thought and interrogation.

Serena’s text has a beautiful clarity, the product of disciplined thinking and writing. Each chapter is elucidated in a different form, sometimes a traditional historical narrative, sometimes a poem, or shaped text, as in ‘Elemental Dust’, and ‘Toxic Agents’. Quotations from different writers, and dictionary definitions punctuate Smith’s own words (‘Rattle. Noise made by paper when it is handled, giving an indication of its stiffness’). The book’s structure, therefore, supports the deconstruction of the process, its language and base material, into digestible, recognisable elements, and keeps the reader alert through these variations of form and content.

Yet the tale told by Heteroglossia is also physical. Smith makes the point that Carswell and Maclise drew their diagrams themselves, held the stone to their bodies, had close physical contact; flesh against stone in parallel with flesh-and-bone medicine. What the artist is at pains to convey is ‘the weight of the limestone, the smell of turpentine and gum Arabic, and the noise of a lithography workshop’. The membranous, organic, chromosomic images work at a cellular level, and this too has resonance; the ‘cell’ of the workshop, in which ‘the lives and bodies embedded in stone lithography’s materials, processes and printed ephemera’ exist.

In a biographical statement, Serena writes, ‘Under scrutiny, images printed from stone silently evidence the lithographic process’. The intention of Heteroglossia is best summed up in the final image, which has the most defined shadow of the stone. Coils and beads are lively, entangled, dark and transparent together, with the beads darkening to the bottom edge, against the pinkish reds and pale yellow of the coils; content and space, density and air.

Interrogating the relationship between image and text is the challenge of the artist’s book: both to the artist and thrown out by the artist. We take on that challenge, as viewers and readers, if we are interested in the dialogue between embodied and cognitive knowledge in our own ‘lived experience’.

Serena Smith, Heteroglossia, stone lithographs with hand offset printed text. Published in 2023 in an edition of 7 individually coloured copies.

An electronic version of Heteroglossia is available to view at:

https://issuu.com/serenajanesmith/docs/glossary_text_for_ issuu

An electronic copy of Ekphrasis may be viewed at:

www.serenasmith.org/a1-gallery2.asp?roomID=12568