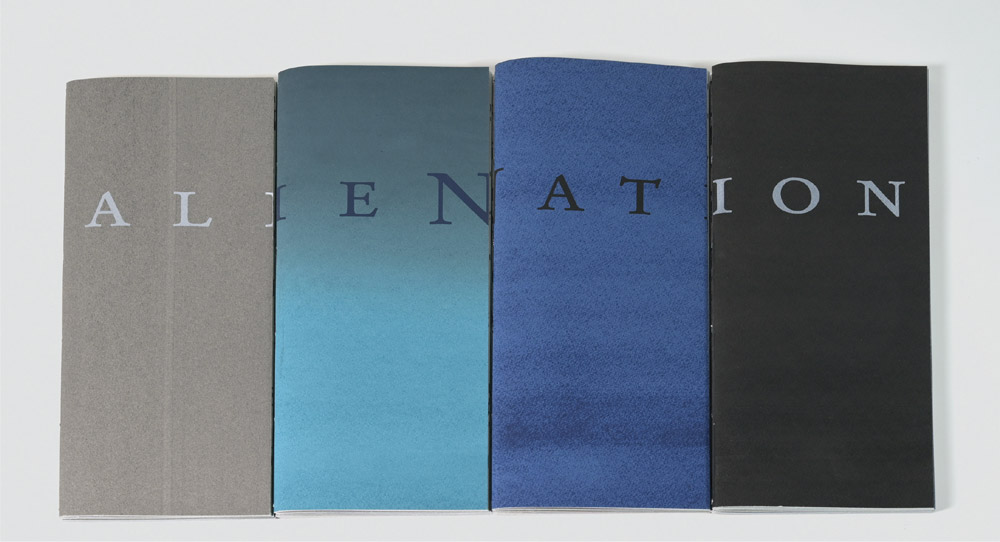

Maureen Cummins, AlieNation/SepaRation (High Falls, NY: Maureen Cummins, 2019). maureencummins.com

Maureen Cummins is a book artist known for engaging difficult and taboo social topics, from slavery to mental illness to the aftermath of September 11th. For her latest artist book, AlieNation/SepaRation, produced as part of Swarthmore College’s Friends, Peace, and Sanctuary Project, Cummins collaborated with Iraqi and Syrian refugees in the Philadelphia area to create a compelling book that combines first-hand accounts of resettlement with imposing typography. The resulting work presents a polyphonic narrative of migration, which allows the reader to accompany the speakers through departure, transit, uncertainty, arrival, discrimination, the immigration ban, and, ultimately, overwhelming loss. The weight of the themes could easily cause a reader to tap out and return to the American pastime of ignoring the consequences of our never-ending military involvements, but Cummins has managed to create an experience of a book that is as engaging as it is emotionally challenging. The book is comprised of four volumes, each with four link-stitched sections, all housed together in a single clear acrylic slipcase. The volumes must be accessed simultaneously for the text—which stretches across the rectos—to be read. The difficulty of the reading experience mimics the intense difficulties of navigating relocation; the reader reaches the end gasping for breath, emotionally wearied, but having survived—just like the narrators themselves.

As is fitting for the subject matter, AlieNation/SepaRation takes up space. The dimensions are striking: the acrylic slipcase containing the four volumes of the book stands nearly 17 1/2 inches tall, a little more than 7 inches wide, and 3 inches deep. When I stood the book on top of my worktable, it was nearly at eye level with me. The manufactured shine of the acrylic contrasts the matte volumes within. This antagonism of textures is repeated between the text and the pages when the volumes are opened. But there is much to appreciate and observe before even opening the book. Viewed from the spine of the slipcase, the volumes stand in a tight row, their sections chained to one another with precisely placed link stitches. Viewed from the fore edge, the pages become vertical bodies, crammed together single file, slightly uneven, organically varied, locked inside their acrylic box.

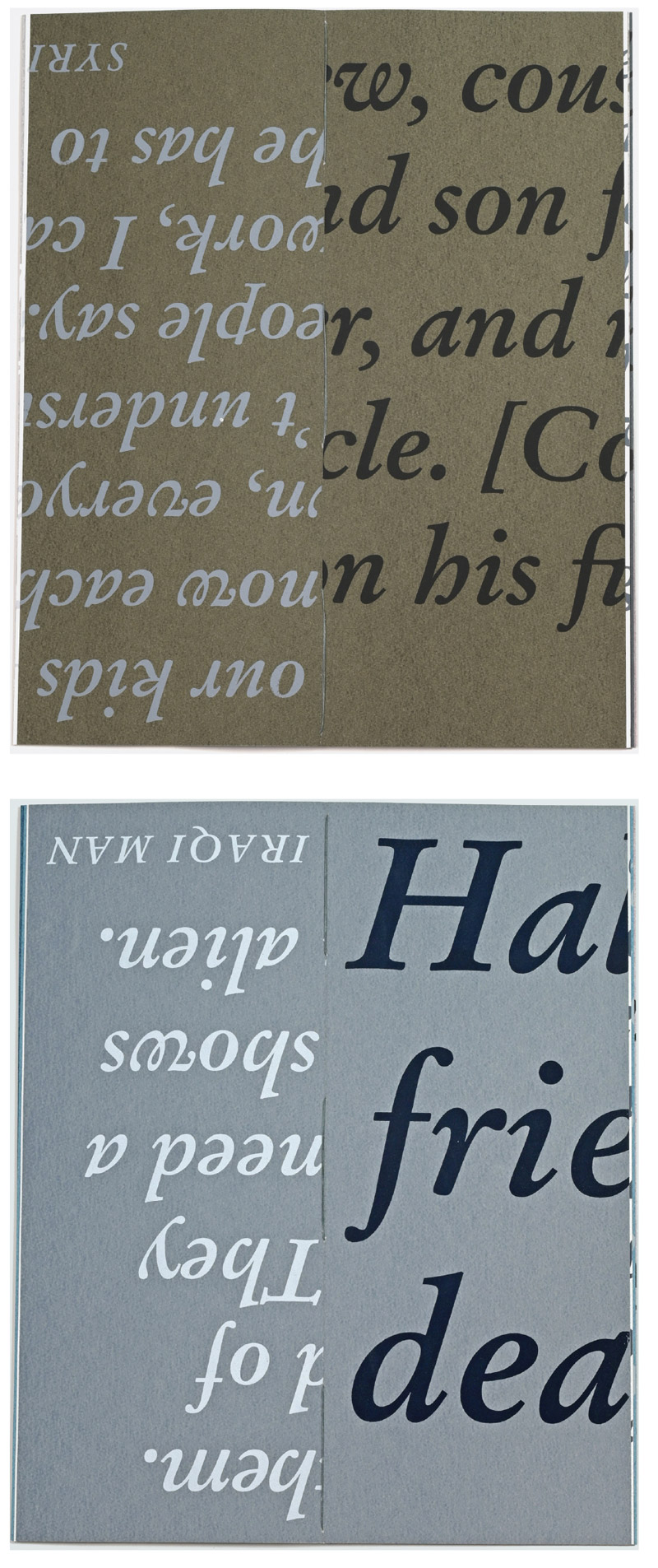

The Friends, Peace, and Sanctuary Project provided Cummins the opportunity to interview Layla Al Hasani, Osama Ahmad Herkel, Yaroub Al Obaidi, and a handful of speakers who chose to remain anonymous. She then used excerpts from those interviews to construct the narrative represented by the words in AlieNation/SepaRation. But the form of the book itself actually expands the scope of the narrative and puts the book directly in conversation with the mission of the project as stated on their website: “Friends, Peace, and Sanctuary explores art’s capacity to build empathy.” The longer I stared at the contents of AlieNation/SepaRation through its slipcase, the more voyeuristic I felt. My vantage point—on the outside, looking in—created an unsettling dynamic: I felt I had the power to free those tightly packed bodies. For the interior of the book to be an effective tool for building empathy, the reader must begin with the United States’ history of demonizing, othering, and subjugating migrants.

As I removed the volumes from the slipcase, I noticed how heavy they were. The color of each volume’s cover is different: blue, black, pink, gray, white. The titles are printed across the four covers inviting the reader to place the books in a row. They too are printed in different colors: dark-blue, white, gray, silver. Yet again, I was struck by how these large volumes take up space and, with their boldly printed words, refuse to be ignored. I was given the instructions: “To read the book, read all the recto pages first (of all four copies set next to each other). Then, when you get to the end, flip all the books around to read the versos.” These same instructions are visually indicated on the prospectus, which shows the volumes lined-up, right-reading, and then backwards. I believe the intended reading is indicated by the continuous printing across the covers, but I suspect someone approaching the book without such guidance would take a couple of extra minutes to figure it out.

I was inhibited in my initial reading of the book by the size of my table. I had to lay the book out with the versos covering the rectos. To read each line of text, I had to hold up the versos to see the rectos, then flip the pages back to start reading the next line. The versos became walls that interrupted the speakers, breaking up their speech like a bad connection. Later, I laid the book out on a large table, approximating a library setting. Instead of walls, the versos created gaps that had to be traversed. The effect was the same. In both cases, the act of reading created frustration; learning how to navigate the familiar landscape of a codex anew became a metaphor for the experiences of the interviewees spoken to the reader across a gap in shared experience.

While readers have to learn to read this book, learning also emerges as an integral part of the speakers’ resettlement story. One of the anonymous collaborators states, “After 2003, we people in Iraq started to learn what it was to be a refugee.” All of this difficulty is balanced by the large, bold, serif typeface screen printed in unexpected colors—occasionally even metallic and sparkling. The elegant simplicity of the typography applied to short, carefully chosen quotes pushes the reader and the narrative forward through the difficult content. At the midway point, when all rectos have been read, the immigration ban is in effect, the future is uncertain, and the reader must shuffle, turn, and reset the book-bodies to make the versos rectos, then continue the story under the next title: SepaRation.

While AlieNation feels like a metaphor for life in a war zone and the logistical and emotional nightmare of forced migration, SepaRation takes on the (equally horrific) monotony of a life unchosen. The chorus of voices quickly learns to anticipate prejudice in their new country. They lose a sense of belonging as their remaining friends and relatives become scattered across the globe, but, eventually, they assert their right to claim the place they live as their home. By the time the reader begins SepaRation, their system for turning the pages and reading—while still appropriately cumbersome—becomes systematized, creating an opportunity to admire the crispness of the screen printed text, and how the changing colors of the pages and text evoke the presence of many speakers.

AlieNation/SepaRation creates a powerful reading experience. I felt trauma-bonded to the speakers, which made me feel terrible returning them to the slipcase-prison. I wanted to know what Layla and Osama and the other speakers were up to now. In my estimation, that means that Cummins was successful in creating connection through art, as has said is the role of art. Is it fair to question whether a book is successful? It’s difficult not to think in those terms when considering a book that has a clearly stated purpose, such as this one. As a reader with a preexisting connection to the resettlement experience, I didn’t initially feel a part of the audience for this book. This book is an empathy primer. It’s trying to convince people who don’t already know that resettlement is traumatic. I actually felt very conflicted about the book at first. To me the book was exploiting that trauma and dehumanizing the participants by erasing the full breadth of their resettlement experience. People who have actually experienced resettlement are often trying to get away from this type of one-note representation. But, I showed it to some people who had zero personal connection to the resettlement experience and their reactions were totally different. They had never thought about resettlement and it made them interested in learning more. That made me consider the book in more general terms, not just from my perspective. In the end, I felt that providing a gateway to an issue is a really big accomplishment for an artists’ book. As I ruminated on this book post-reading, Quassem Suleimani was assassinated. The importance of this book should not be underestimated. The need for artistic work that offers a praxis of empathy in the way that AlieNation/SepaRation does is absolutely necessary right now.